A Preliminary Investigation of the Benefits and Barriers to Implementing Health Information Technology in Medical Clinics

Dr Amy Chesser PhD1, Dr Nikki Woods PhD2, Dr Traci Hart PhD2, Dr Jennifer Wipperman MD1

1University of Kansas School of Medicine, Wichita, USA. 2Wichita State University, Wichita, USA

Corresponding Author: achesser@kumc.edu

Journal MTM 1:3:32-39, 2012

DOI:10.7309/jmtm.20

Background: The successful integration of mobile information technology (IT) and existing health information technology (HIT) requires a critical evaluation of factors that may impede implementation and end-user perceptions of new technology.

Purpose: Using a mixed-method approach researchers interviewed and issued questionnaires to a family medicine faculty and residents to ascertain: 1) usability of iPad features and functions in a practice setting, and 2) perceptions of barriers to and support for implementation of HIT in a clinical setting.

Methods: Two faculty physicians and one resident were interviewed to discuss the HIT infrastructure for the clinical site, as well as attitudes and preferences about iPad usability. Qualitative data was transcribed and analyzed. Resident and faculty physicians (n=42) from a family medicine residency completed an American Medical Association survey on HIT readiness. Descriptive and non-parametric statistics were tabulated.

Results: Both interview and survey participants reported individual readiness for HIT adoption, while listing environmental barriers. Interview participants also described physical and software features of the iPad they would find useful in practice. Survey respondents reported clinical staff readiness as a strength for adoption of HIT.

Conclusion: Participants reported readiness to integrate HIT into clinical practice and have a clear idea of useful device features. HIT adoption may be hampered by environmental factors, and future research should focus in this area.

Introduction

With technology advancing at a rapid rate, health care professionals face numerous opportunities and options for incorporating health information technology (HIT) into practice. Electronic-based health information has been shown to decrease redundant treatments and improve decision-making.1-41. Bates D, Kuperman G, Rittenberg E, Teich J, Fiskio J, Ma'Luf N, et al. A randomized trial of a computer-based intervention to reduce utilization of redundant laboratory tests. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):144-50.

2. Bates D. Physicians and ambulatory electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(5):1180.

3. Bates D, Ebell M, Gotlieb E, Zapp J, Mullins H. A proposal for electronic medical records in US primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(1):1.

4. Liu J, Wyatt J, Altman D. Decision tools in health care: focus on the problem, not the solution. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6(1):4. One device demonstrating promise in the medical setting is the Apple iPad tablet, the industry leader in terms of available applications (apps).55. Robertson I, Miles E, Bloor J. The iPad and medicine. 2010 cited 2011 January 12; Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20001584. Since its unveiling in early 2010, the iPad has been adopted by the medical community for education,6-86. Cannon C. Cardiology's move online—and onto my iPad. The Lancet. 2010;376(9740):505-6.

7. Rohrich RJ, Sullivan D, Tynan E, Abramson K. Introducing the new PRS iPad app: the new world of plastic surgery education. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Sep;128(3):799-802.

8. Turnock M. Undergraduate medical education: Is there an iPad app for that? Univ Toronto Med J. 2011;88(2):69-71.surgical assistance,99. Volonte F, Robert JH, Ratib O, Triponez F. A lung segmentectomy performed with 3D reconstruction images available on the operating table with an iPad. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jun;12(6):1066-8. and provider-patient communication assistance.1010. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, Bakken S, Feiner S, Boyer A, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428-35.

For both physicians and patients, the adoption of new HIT such as the iPad, is determined by a combination of environmental (e.g., integration across organizational boundaries, interface with multiple electronic health record (EHR) systems, legal concerns regarding patient privacy) and individual factors (e.g., daily work flow issues, concerns about control, autonomy, authority and trust regarding the use of individual information, and motivation to change to another device).1111. Tang P, Ash J, Bates D, Overhage J, Sands D. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):121. Family medicine doctors often work autonomously, allowing them the opportunity to adopt technology in a more flexible fashion.55. Robertson I, Miles E, Bloor J. The iPad and medicine. 2010 cited 2011 January 12; Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20001584. To efficiently integrate HIT into this setting, it is necessary to evaluate what may impede implementation such as integrating workforce IT systems with clinical needs and patients level of e-health literacy or perceptions of usefulness.55. Robertson I, Miles E, Bloor J. The iPad and medicine. 2010 cited 2011 January 12; Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20001584., 1212. Norman C, Skinner H. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res. 2006; 8(2):e9., 1313. Or C, Karsh B, editors. The patient technology acceptance model (PTAM) for homecare patients with chronic illness2006: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

Since HIT has the potential to positively influence communication and health outcomes, it is important to understand the process of HIT adoption in order to effectively promote its use. Little is known about the environmental and individual factors influencing HIT adoption.1414. Holden RJ, Karsh BT. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform. 2010 Feb;43(1):159-72. This mixed-method study was conducted to ascertain: 1) understanding of specific HIT features and functions (individual factors), and 2) perceptions of barriers to and support for implementation of HIT in a practice setting (environmental factors).

Methods

Participants

This study included resident and faculty physicians from a family medicine residency ambulatory office located in an urban Midwestern community that had recently implemented the iPad into practice (< 1 year use). Prior to implementing the iPad, ten faculty members and resident physicians were asked to pilot the technology for one year. During this time the physicians were encouraged to download and use any free applications for clinical use. The iPads were encouraged for use during clinical encounters and for activities that would enhance workflow such as for charting. Additionally, the iPad could be taken home to use for work purposes at the physician’s discretion. A random selection of individuals who had piloted the iPad from different specialties participated in the in-depth interviews for this study.

Procedures

The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board. This two-part study included a paper-based survey and in-depth interviews with physicians. All faculty and resident physicians were eligible to participate. The inclusion criteria included: (1) English-speaking, (2) faculty or resident physician, (3) able to use a computer; and (4) able to provide informed consent.

Surveys – To assess HIT readiness, a modified version of the previously validated AMA survey on readinesswas used.1515. American Medical Association. Health IT readiness survey. 2011 cited 2011 January 12; Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/health-information-technology/implementing-health-it/prepare.page. The authors selected the AMA survey due to experience using the tool when consulting with agencies on HIT readiness. The survey was modified by changing the language in a few of the statements and removing two statements in an effort to make the survey more applicable to the study population. Participants were recruited and completed the assessment anonymously during noon conferences over a three month period from February to May 2011. The survey consisted of 22 items designed to assess physician attitudes and knowledge of technology use in the clinical setting. No incentive was provided to interview or survey participants. In-depth interviews with one-on-one facilitators lasted approximately 30 minutes. Each session was led by a trained facilitator and staffed by at least one note taker. After each interview, the team reviewed the findings of the session. Descriptive statistics were tabulated from survey data. The continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann Whitney test for non-normal distributions. All statistical tests were two-tailed and alpha =.05.

In-depth interviews – Transcribed notes from each interview were analyzed according to the qualitative methods. The notes were transcribed into an electronic version. Research team members cut full quotes that concisely summarized points and used them to describe emergent themes. Emergent themes were categorized and transcripts from each interview were combined and compared.1616. Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW, editors. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007.

Results

Surveys

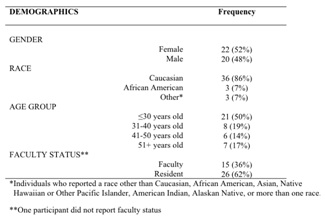

Forty-two (n=42) resident and faculty physicians from a family medicine residency ambulatory office completed the survey.The majority of participants were white (86%) and were 21-30 years old (50%). Resident physicians represented 63% of participants. Gender of participants was evenly distributed, with 48% male and 52% female. All demographics are reported in Table 1.

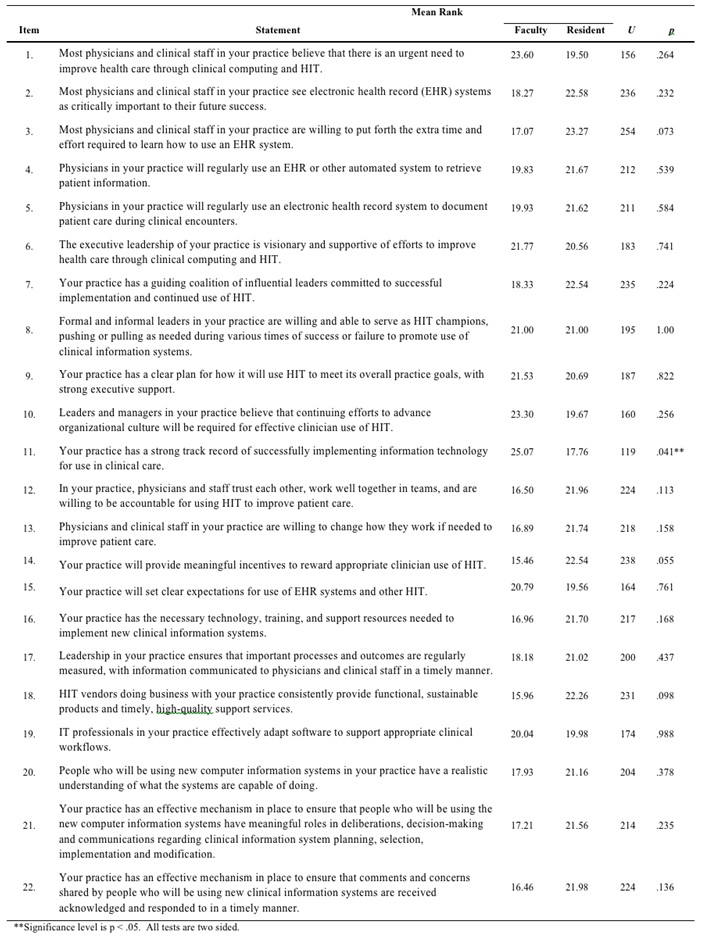

Twenty-two statements regarding readiness to implement HIT were included in the paper-based survey. Participants were asked to indicate a response to each statement on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All results and statements are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1 -Demographic Information of Survey Participants (n = 42)

Respondents most strongly agreed with statements that fell within three factors, including HIT use, readiness, and physician and staff perceptions of HIT. Items with the highest mean rating included “Physicians in your practice will regularly use an [electronic health record] EHR or other automated system to retrieve patient information” (mean 4.69) and “Physicians in your practice will regularly use an electronic health record system to document patient care during clinical encounters” (mean=4.67).

In terms of workplace relationships affecting HIT, the items “Physicians and clinical staff in your practice are willing to change how they work if needed to improve patient care,” (mean=4.03); “In your practice, physicians and staff trust each other, work well together in teams, and are willing to be accountable for using HIT to improve patient care,” (mean=4.00); and “Most physicians and clinical staff in your practice see EHR systems as critically important to their future success,” (mean=3.93) were other top agreement statements (Table 2).The items with the lowest mean ratings were “Your practice will provide meaningful incentives to reward appropriate clinician use of HIT” (mean=2.78) and “HIT vendors doing business with your practice consistently provide functional, sustainable products and timely, high-quality support services” (mean=2.63) (Table 2).

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare faculty and resident responses to each survey question. Faculty and resident physicians reported a statistically significant difference on one question, “Your practice has a strong track record of successfully implementing information technology for use in clinical care.” Faculty reported a mean value of 4.07 and residents reported 3.32 (U=119, p=.041). These findings are reported in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences based on gender or by age when comparing those 30 years old and under to those over 31 years and older.

In-depth interviews

Two faculty physicians (n=2) and one resident physician (n=1) were interviewed to discuss the HIT infrastructure within which they worked, as well as attitudes and preferences about iPad usability. Interview responses included themes of HIT infrastructure, iPad functionality, and iPad potential. Participants indicated the presence of general iPad security issues, as well as compatibility with current electronic health records (EHR), as barriers to successful integration of the iPad into clinical practice. Interviewees suggested that support from a dedicated IT department would be necessary to overcome these. One participant concluded, “IT has to be behind whatever devices you use.”

In terms of functionality, participants indicated that both physical design characteristics and software functions of the iPad were important. Features such as light weight, small size, touch screen, camera, long battery life, and ease of charging were deemed helpful for a practice setting. Necessary software functions included simple interface, video conference applications, speed, and access to electronic medical records. At the time of this study, the iPad’s inability to multitask was identified as a limitation, “Well, you can’t multitask like you can in windows.”

Participants ended by expanding on potential uses for the technology in the clinic including educational videos for patients, the possibility of improving the quality and amount of physician notes in patient files, and enhanced communication between providers and patients (e.g., displaying images such as the high fidelity x-rays, anatomically correct drawings provided by various apps, and offering ability to print patient resources in real-time).

Table 2 – Survey Results Ranked by Mean

Table 3 -Comparison of Faculty and Resident Survey Responses

Discussion

Participants from the in-depth interviews highlighted several important factors about the implementation of HIT devices. Specifically, how physicians use the iPad within clinical care was explored. First, the device was seen as a compliment to the existing electronic infrastructure. This could have important implications for primary care providers as the current infrastructure is examined and enhancements are planned. In the future, the iPad could permit continuous data entry into EHR systems as well as the addition of photograph documentation to support notes.

Results from the survey indicated that physicians regularly used their electronic health record system during clinical encounters to retrieve patient information. Physicians indicated they were willing to change their behaviors to improve patient care, and believed they work in a supportive staff environment. These findings suggest that in order to successfully implement and sustain HIT, primary care clinics must address aspects of HIT use that extend beyond the device itself. Responses to the survey indicate environments conducive to the use of HIT may require members that see the tool as important to improving patient care and whose work environment contains trust and cooperation among co-workers. Trust has been identified as necessary for producing a successful work environment and this becomes especially important during organizational transitions or transformations.17, 1817. Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J. The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses' work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Manage Rev. 2001 Summer;26(3):7-23.

18. Whitney J. The Trust Factor. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.

The iPad itself possessed physical and software features that made it useful to the physician participants in this study. However, the device’s limitations included inability to multitask and the compatibility with secure networks (or inability to use 3G network within a secure system). Interview participants shared concerns that these issues with security and compatibility could potentially prevent the adoption of new HIT in many medical centers.

Limitations

There were several limitations identified in this study. The population was limited to a single clinical site in a Midwestern location and no comparison group was included in the study. Participants included mostly Caucasians, 30 years of age or less. Despite these limitations, this study provides one statement in a larger conversation about the potential barriers and favorable conditions for successful integration of HIT into the clinical setting and indicates a clear direction for future research on collaboration between IT programs and clinical staff and the requisite environmental work conditions needed for successful HIT implementation.

This study was not sufficiently powered and only univariate statistics were used. The lack of effect size limits the interpretation of the HIT readiness survey findings. For the qualitative data, saturation was not reached due to the small number of participants interviewed. This study, although underpowered, serves as a preliminary investigation to assess the use of the Apple iPad in a clinical setting as a part of patient care. The findings were valuable to the organization that implemented use of the iPad and has aided in their logistical determinations for more widespread implementation of this tool.

There is the possibility of bias from the sample of faculty and residents used for the in-depth interviews as they also participated in piloting the iPad. The sample used for this study was a random selection of the individuals who piloted the iPad and who were instrumental in assisting with the implementation of the iPad for the study clinic. It was the decision of the research team to gather the perception and opinions of this group rather than the group at large, as the team thought that their experiences would provide a richer context of the usability of the iPad’s features and functions as well as perceived barriers and supports in a medical clinic.

Conclusion

Health information technology can improve a physician’s access to EHRs which has positive benefits for treatment and decision making1-41. Bates D, Kuperman G, Rittenberg E, Teich J, Fiskio J, Ma'Luf N, et al. A randomized trial of a computer-based intervention to reduce utilization of redundant laboratory tests. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):144-50.

2. Bates D. Physicians and ambulatory electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(5):1180.

3. Bates D, Ebell M, Gotlieb E, Zapp J, Mullins H. A proposal for electronic medical records in US primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(1):1.

4. Liu J, Wyatt J, Altman D. Decision tools in health care: focus on the problem, not the solution. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6(1):4.

and may provide an improved method for connecting and educating patients. This study found that the Apple iPad, was readily adopted into practice receiving primarily favorable remarks from study participants. Supports for the use of HIT involved a mixture of features, (camera, light weight, etc.) functionality, (easy-to-use interface) and the environment in which the device was used (trust, cooperation, and understanding the relevance of the tool). Barriers to the implantation of the iPad included the need for dedicated IT assistance to overcome identified security and compatibility issues and the inability to multitask. Future research of HIT needs to take place not in the study of physician understanding and readiness, but in the physician’s work environment. Communication between physicians, hospital administration, vendors and dedicated IT professionals will be essential, as the needs for security and functionality are balanced. The potential exists for HIT to positively impact health and patient-provider communication, but before HIT such as the Apple iPad is readily adopted in the clinical setting, certain barriers should be identified and addressed.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Eric McDaniel and Jared Reyes, and Aron Fast, MD for their contributions that aided in the completion of this study. This research was supported in part by funding from a Level I Dean’s Grant awarded by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita. All study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation were solely developed and conducted by the authors. Further, all recommendations and conclusions expressed in thismaterial are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agency.

References

1. Bates D, Kuperman G, Rittenberg E, Teich J, Fiskio J, Ma’Luf N, et al. A randomized trial of a computer-based intervention to reduce utilization of redundant laboratory tests. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):144-50. ![]()

2. Bates D. Physicians and ambulatory electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(5):1180. ![]()

3. Bates D, Ebell M, Gotlieb E, Zapp J, Mullins H. A proposal for electronic medical records in US primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(1):1. ![]()

4. Liu J, Wyatt J, Altman D. Decision tools in health care: focus on the problem, not the solution. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2006;6(1):4. ![]()

5. Robertson I, Miles E, Bloor J. The iPad and medicine. 2010 [cited 2011 January 12]; Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20001584.

6. Cannon C. Cardiology’s move online—and onto my iPad. The Lancet. 2010;376(9740):505-6. ![]()

7. Rohrich RJ, Sullivan D, Tynan E, Abramson K. Introducing the new PRS iPad app: the new world of plastic surgery education. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Sep;128(3):799-802. ![]()

8. Turnock M. Undergraduate medical education: Is there an iPad app for that? Univ Toronto Med J. 2011;88(2):69-71.

9. Volonte F, Robert JH, Ratib O, Triponez F. A lung segmentectomy performed with 3D reconstruction images available on the operating table with an iPad. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jun;12(6):1066-8. ![]()

10. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, Bakken S, Feiner S, Boyer A, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428-35.

11. Tang P, Ash J, Bates D, Overhage J, Sands D. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):121. ![]()

12. Norman C, Skinner H. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res. 2006; 8(2):e9. ![]()

13. Or C, Karsh B, editors. The patient technology acceptance model (PTAM) for homecare patients with chronic illness2006: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society.

14. Holden RJ, Karsh BT. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform. 2010 Feb;43(1):159-72. ![]()

15. American Medical Association. Health IT readiness survey. 2011 [cited 2011 January 12]; Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/health-information-technology/implementing-health-it/prepare.page.

16. Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW, editors. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007.

17. Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J. The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Manage Rev. 2001 Summer;26(3):7-23.

18. Whitney J. The Trust Factor. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.