Epilepsy at a glance: a mobile medical record

Melissa Reider-Demer DNP, MN, CPNP1

1Brandman University Irvine, Pediatric Neurology, Children Hospital Los Angeles, USA

Corresponding Author: mrdemer@mednet.ucla.edu

Journal MTM 2:2:3-7, 2013

http://dx.doi.org/10.7309/jmtm.2.2.2

Introduction: Inefficient transfer of health information among facilities fragments care and motivates duplicate interventions. This pilot study was designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of “Epilepsy at a Glance” (EAG), a portable medical record that contains medical records of children with epilepsy. This mobile tool enables medical providers to expedite information sharing to decrease fragmentation of patient care.

Methods: This randomized study included 30 children with epilepsy, 15 each in the experimental and control groups. The experimental group received the EAG while the control group received usual care and a medical alert bracelet at the end of the study. At the beginning and end of the study, participants completed a written survey about their contact with outside providers of epilepsy care. The experimental group was also surveyed at two follow-up clinical visits to determine the usage and impact of the EAG.

Results: The experimental group brought the EAG to over 90% of outside care encounters. More than 80% of primary care, 68% of urgent care, and 100% of emergency room providers viewed the EAG at the point of care. No outside provider who viewed the EAG inappropriately altered the established long term plan of care or performed duplicate testing. Patients and outside providers were enthusiastic about the value of the EAG.

Conclusions: This pilot study demonstrates the value of EAG usage by patients and medical providers, and suggests a promising use of transferring patient medical information using mobile technology. Future studies should be performed with larger groups using EAG or alternative devices to document improved care and reduction in test duplication.

Introduction

Care for children with epilepsy can be overwhelming for patients and their families. The level of intervention required from medical providers has increased due to disease complexity and needs of patients and families. Primary care providers, neurologists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants must schedule frequent office visits to follow patients and monitor diagnostic tests. Current practice is also influenced by demands and restrictions of managed care and third party payers,1 making it increasingly difficult for medical providers to provide adequate and consistent treatment. For instance, after seeing one medical provider for years, a patient may be re-assigned to a new provider because of changes in insurance coverage. Insurance restrictions may require that diagnostic tests be performed at a location different from that of the medical provider. Similarly, a patient in an epileptic crisis may be brought to an outside facility where medical personnel are unfamiliar with the patient’s medical history, necessitating redundant testing and possibly motivating inconsistent changes in management.

While the medical system continues to face cost constraints, patients’ diagnoses become increasingly complex. The use of medical information technology is a reasonable tool to improve patient management2. In order to meet today’s expectations for patient care, methods of accessing and transferring medical information must change to enable patients to access and transfer their medical information.

During most neurology clinic visits, a discussion takes place among the patients, their families, and the medical provider, clarifying the level of the patient’s seizure control and defining treatment goals. A plan of care is developed and is evaluated at follow-up visits. If an outside medical provider unfamiliar with these goals cares for the patient between visits, this plan of care may be modified from the long-term approach. One solution is to allow patients and their families access to their medical information and plans of care. This information can be stored on a widely accessible universal serial bus (USB) memory device. This device is small enough to be attached to a key chain carried constantly by the patient. By making available medical history and other useful information such as demographics, the memory device could facilitate continuity in patient care. While earlier versions of this portable electronic medical record did not provide as much detail as a complete medical record, newer versions can provide a treating provider with the necessary information to adequately manage patients without duplicating medical service3. These devices are typically encrypted and password protected to ensure that a patient’s medical and demographic information remain private. The present study was designed to assess the usability of accessing and transferring the plan of care and neurological healthcare information of a child with epilepsy stored on the EAG.

Methods and Implementation

This pilot study was randomized and controlled, evaluating 30 children with epilepsy followed over a five month period. Participants were patients at the Neurology Clinic of the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (CHLA) but also visited other facilities and providers, such as emergency rooms, more than once a year. The exclusion criteria were: inability to speak English or Spanish; parents or guardians unable to provide consent; Assignment was by a random number table so that 15 participants received the EAG and 15 did not. Each participant was assigned a study number to ensure confidentiality. The EAG was encrypted and password protected to safeguard confidentially. The encryption was implemented through the encryption feature of Adobe Acrobat Pro. This study received Institutional Review Board, (IRB) approval from CHLA and Brandman University.

It was hypothesized that use of the EAG containing a summary of medical history and current plan of care for children with epilepsy would improve continuity of care above existing practice.

The EAG included the individual patient’s demographic, general medical and relevant neurological information. Specifically, the patient’s neurological diagnoses; seizure semiology; current vagal nerve stimulator (VNS) settings; a listing of past and current anti-epileptic medications and their dosages; most recent electroencephalograph (EEG), magnetic resonance (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography (PET) scan reports; management strategies for status epilepticus; known drug allergies; and neurology and primary care provider contact information.

To recruit participants, a medical assistant at the CHLA Neurology Clinic presented a flyer outlining information about the study to eligible patients and their families during their regularly scheduled visits. A flyer was also displayed in the clinic’s waiting room. The nurse practitioner principal investigator approached the parent or guardian to determine ability to understand and willingness to participate in the study. Upon agreement to enroll in the study, consent was obtained. This survey was comprised of seven questions addressing: the average number of seizures experienced; frequency of seeking medical care from outside facilities; availability of a primary care provider; school absences because of seizures; parental work absences due to the child’s seizures; and availability of a nurse at the school attended. This survey was not evaluated against a validation tool. The study group received an EAG at the beginning of the study; the control group received a medical alert bracelet at the end of the study. At the time of the study, none of the patients in the control group wore a medical alert bracelet.

The questionnaire for the study group included questions evaluating the utility of the EAG when used between scheduled visits to the CHLA Neurology Clinic. The study group completed this questionnaire at two subsequent clinic visits. There were two follow-up study visits scheduled at approximately two-month intervals after the initial study visit. The post-implementation questionnaire evaluated the effectiveness of the EAG as compared to the current practice of verbalizing the patient’s history to the outside medical provider. The questionnaire indicated if the EAG was presented to outside healthcare providers, and if outside healthcare providers viewed the EAG and implement the suggested plans of care. At these clinic visits, the information in the EAG was updated as needed.

Informed Consent

Children unable to understand the concept of “voluntary” or “research” after age-appropriate explanations were deemed unable to give informed consent. Young adults (18–21 years) were enrolled into the study only if able to read the consent with basic assistance and verbalize understanding of the nature of the procedures. Those unable to read or understand the consent were enrolled only upon consent of the parent or legal guardian. The study consents were offered in English and Spanish. Interpreters were available.

The study group received an information card to carry with them explaining the purpose of the EAG. During the course of the study, parents were asked to provide the information cards to any outside medical care provider with whom they interfaced.

Each patient within the study group carried the EAG attached to a key chain. The control group received a medical alert bracelet upon study completion. Both groups received a $10.00 gift certificate at the end of the study. The EAG data was stored as an encrypted, password protected, “read only” portable document format (PDF) file on a USB memory so that patient data was modifiable only by the study staff, which ensured the safety of the information that was being transferred throughout the study. To ensure patient confidentiality, no one other than the individuals with the password could access the information held within the USB memory drive. Once the study was completed, the patient’s information was destroyed per their request. Future studies should allow providers to input and transfer patient information among the respective medical providers.

Each family in the study group was given a notepad at the start of the study and asked to record any medical visits outside of the CHLA Neurology Clinic, including the date and institution where they received medical attention; the reason for the outside medical attention; the name of the outside medical provider; the telephone number of the outside institution providing care; and any other information believed important. Families were asked to bring this notebook with them to each clinical visit and to complete a medical release form, if needed, to obtain their outside medical records.

Results

Families and patients were willing to participate in the study, accepted randomization, and were reasonably compliant with the study. There was a waiting list to join this study. Although several patients who expressed an interest in being part of the study did not meet inclusion criteria, they indicated they would be willing to participate in similar studies in the future if they were applicable to their child’s needs.

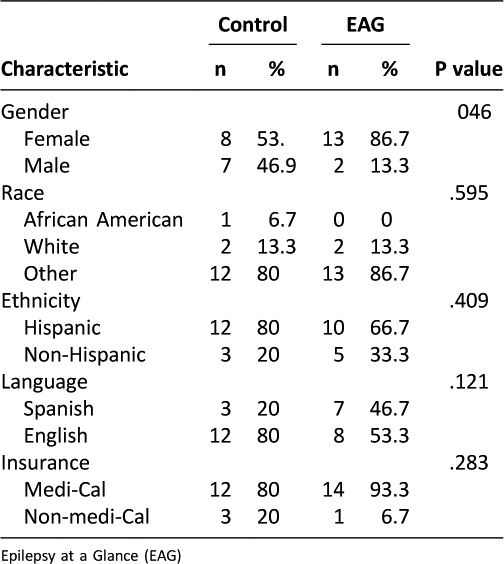

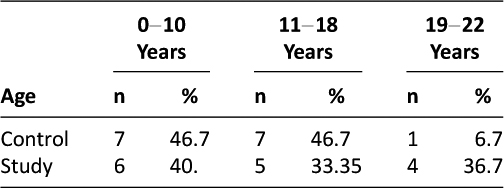

Participants ranged in age from 0-22 years, with the majority under age 10 years, as demonstrated in (Table 2). Control and study groups were unequal at the study start for gender and primary language, as shown in (Table 1). Data on the frequency of using the EAG device was also collected; positive outcomes of the use of the EAG are demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 1: Participant Demographics

Table 2: Participant Age Ranges

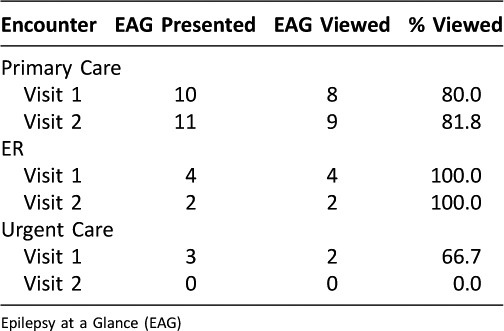

Table 3: Frequency of EAG being viewed by medical professional when presented

One of the 15 study group participants was lost to follow-up; the remaining 14 were assessed at two subsequent study visits. Fourteen of the 15 study participants (90%) presented their EAGs to their outside medical providers. During the first study visit, eight out of 10 (80%) participants reported that they presented the EAG to their medical providers, who viewed the information on the EAG. During the second visit, nine out of 11 (81.8%) reported that they presented EAGs to the primary care providers, all of whom viewed the information on the EAGs.

Among the 14 study group participants, data from the first study visit showed that 4/4 (100%) presented EAGs to their outside emergency room providers, all of whom viewed the EAGs. Between the first and second study visits, 2/2 (100%) emergency department medical providers viewed the EAGs. Among the 14 study group participants, three reported that they presented EAGs to their urgent care providers. Of the three such providers, two (67%) viewed the EAGs. No participant visited an urgent care provider between the first and second study visits.

Patients reported that the EAG was also presented to dentists, orthopedists, and school nurses. These providers stated that the information on the EAG was helpful. In one case, a school nurse was able to verify the seizure medication dose required by a patient who was on a field trip, and was informed of appropriate management for status epilecticus in that child. The nurse indicated that she typically had such information on file, but with over a thousand students, the EAG was more accurate and timely. Outside providers noted that it was useful to have the individual neurological information in the EAG at the point of care. There were no reported unintended effects associated with the use of this device and no negative feedback was provided by the participants or outside medical providers regarding the EAG.

Outside medical providers were very willing to use the device (Table 3). Over 80% of primary care providers and 68% of urgent care providers viewed the information on the EAG when it was presented to them, as did 100% of emergency department providers. All of the 10 study participants who presented EAGs to outside treating facilities reported the names of the outside facilities and the treating providers and filled out releases that allowed the study to obtain medical records from outside facilities. The study received feedback from 6/10 (60%) of treating outside providers. These providers verified their use of the EAG and indicated that they followed the proposed patient plan of care and did not order further studies because of the information in the EAG.

After using the EAG, emergency department medical providers expressed an interest in it and were satisfied to have the information available. Because they had the most recent information about the patient’s neurological status, outside providers avoided performing additional diagnostic tests, and made no changes in neurological plans of care.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the EAG is a valid alternative to the conventional way of accessing and transferring medical information. The EAG emerged as a useful, practical, and innovative tool for improving medical information access and transfer, and improving patient care outcomes. Patients were willing to participate, accept randomization, and use the EAG, which supports the utilization of a novel device by medical providers in various settings.

Technological options such as cellular phones, portable digital memory devices, and digital medical alert bracelets can be utilized to improve communication and facilitate access to health information. These new alternatives enable medical care providers to better access and transfer medical information, and to store it in an accessible, confidential, and practical place3. Patients seem willing and ready to use communication technologies such as mobile phones and the internet4. Mobile technology can provide personalized messaging and efficient data collection for health management and promotion2. As hospitals acquire electronic health-record systems, wireless telephones and other technological devices will likely become an integral part of the architecture5.

There are important limitations to discuss in this study. Though randomization was utilized, the difference in baseline population characteristics between the two groups meant that outcome data could not be meaningfully compared using quantitative analysis. A sample size of 30 participants does not fully represent the epilepsy population; a larger population would be required to fully represent the patient spectrum. The current EAG did not contain images of radiological or EEG data, although it could be included in the future. Another limitation was that the information collected from the questionnaires was dependent on participant answers, which could have influenced external validity. A different mobile device such as a digital medical alert bracelet might also be considered. This device allows medical providers access to essential information without requiring a password in emergency situations, and a secondary option that requires a password for more extensive medical information enabling the medical provider to implement less urgent medical intervention at the point of care.

Conclusion

Mobile technology is the future of for transfer of patient medical information. This study demonstrated the utility of the EAG, a patient-carried, digital medical record available to medical providers in primary, emergency, and urgent care settings. Availability of patient medical information at the point of care allowed providers to appropriately manage patients, make educated decisions about care, and avoid duplicating tests. The present study shows promise for improvements in accessing and transferring medical information.

Disclosure: Funded in part by The Epilepsy Foundation of Greater Los Angeles.

References

1. Lavizzo-Mourey R. Malcolm Peterson Honor Lecture. 2006.

2. Blake H. Innovation in practice: mobile phone technology in patient care. Br J Community Nurs 2008;13:160-162–5.

3. Blake H. Mobile phone technology in chronic disease management. Nurs Stand 2008;23:43-6.

4. Fonseca JA, Costa-Pereira A, Delgado L, et al. Asthma patients are willing to use mobile and web technologies to support self-management. Allergy 2006;61:389-90. ![]()

5. Page D. Technology: cell phones are quickly becoming cutting-edge medical devices. Hosp Health Netw. 2008;82:13.