Medical students’ perceptions regarding the impact of mobile medical applications on their clinical practice

Kwee Choy Koh, MMed, MBBS1, Jun Kit Wan2, Sivasanggari Selvanathan2, Chithralekha Vivekananda2, Gan Yi Lee2, Chun Tau Ng2

1Senior lecturer, Department of Medicine, International Medical University, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, and consultant infectious disease physician, Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; 23rd year undergraduate medical student, International Medical University, Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Corresponding Author: kweechoy_koh@imu.edu.my

Journal MTM 3:1:46–53, 2014

Background; Medical apps on smart devices are popular among medical students. However, the impact of medical apps on clinical practice is relatively less known.

Aims: To study the prevalence of medical app usage among medical students and assess its impact on clinical practice.

Method: One hundred fifty-five first year medical students of the International Medical University, Malaysia completed an anonymous questionnaire designed to explore demographic parameters, types of smart devices owned and the medical apps installed on the smart devices; and the frequency and purpose of usage of the apps. The students’ perception regarding medical apps, the impact of medical apps on clinical practice and the characteristics of an ideal medical app were explored.

Results: About 88% of medical students reported owning a smart device and 87.5% had medical apps installed on their smart devices. Most students reported positive perceptions towards medical apps and agreed they have positive impact on their studies and clinical practice. However, the medical students reported little awareness about the potential breach of patient confidentiality with the use of these apps.

Conclusion: There is high prevalence of smart devices and medical apps usage among first year clinical medical students with positive perception regarding its usage and impact on their clinical practice. Medical schools should encourage the use of medical apps among medical students with strategies put in place to safeguard patient confidentiality.

Introduction

The world’s first smart phone was introduced in 1994 and since then the number of people using smart phones have been increasing. Medical applications (apps) that are downloadable onto smart devices’ operating systems such as iOS or Android are increasingly becoming popular among clinicians.1 There are currently more than 13,000 medical apps available for downloading online.2 A recent survey conducted in the United Kingdom showed 84% of medical students believed that smart devices were a useful addition to their medical education. 3

According to an Epocrates survey, more than 40% of medical students indicated they turn to smartphone medical apps as their first choice of reference.4 Factors which contributed to the increased use of medical apps include convenience, cost, ease of use, comprehensive coverage, variety and utility. The types of medical apps favoured by medical students fall mainly into the category of clinical reference, drug reference, diagnosis help and medical calculators.5 It is estimated that 80% of physicians own and use smartphones6, as such the incorporation of these tools into medical schools to help guide their appropriate use is vital.

Many medical universities have embraced this new technology as part of training of their medical students by promoting medical apps resources on their websites and maintaining licenses for these apps. 7–10 At the International Medical University (IMU) in Malaysia, the license for only one mobile medical app, Dynamed; is maintained by the University for use by its staff and medical students. However, the prevalence of smart device and medical apps usage among medical students is unknown. We conducted this study to explore the uptake and usage of smart devices and medical apps among medical students and their perceptions on the impact of medical apps on their clinical practice.

Method

Student population

We conducted the survey at the clinical school of the International Medical University (IMU) in the city of Seremban, State of Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. The participants in the study were medical students in their first year of clinical training totalling 169 students. In the first clinical year, these students were rotated within several postings which included the department of internal medicine, surgery, family medicine, dermatology, geriatric medicine, rehabilitation medicine, orthopaedic, psychiatry, radiology, emergency medicine, ophthalmology and ear-nose-and-throat. Apart from clinical sessions such as ward work, clinics, bedside teachings and surgical procedures in the operating theatre, their postings also included lectures; clinical task based learning (TBL) sessions and medical seminars. Medical information for these students was mainly accessed from three sources, namely medical textbooks, online websites and medical apps on smart devices. Access to Wi-Fi was freely available within the grounds of the university and hospital while smart devices with paid-for-3G service can also access the internet via 3G within these institutions.

Questionnaire

We collected data using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was divided into four parts. Part one consisted of questions designed to gather demographic parameters of the study sample such as gender, ethnic group, ownership and types of smart devices, means of internet access on the smart devices (Wi-Fi, 3G or both), installation of medical apps on smart devices (free or paid), frequency and purpose of medical apps usage. The students were also asked to identify the medical apps installed on their smart devices using a predetermined check-list containing a list of popular and reputable medical apps.11 Part two of the questionnaire contained 12 questions designed to evaluate medical students’ belief regarding medical apps, chiefly in comparing medical apps to traditional sources of medical knowledge such as medical textbooks.

Part three of the questionnaire contained 11 questions designed to assess the impact of medical apps on the medical students’ clinical practice based on the perception of the students while the final part of the questionnaire contained 10 questions which were designed to assess the perception of medical students on the qualities or characteristics of an ideal medical app. The questions were formulated from a list of desired qualities in medical apps which has been published earlier.11

A 5-point-Likert scale was used for scoring purpose for each question in part two to part four of the questionnaire. A numerical value was assigned to each of the 5-points where “1” was for “strongly disagree”, “2” for “disagree”, “3” for “unsure”, “4” for “agree” while “5” was the score for “strongly agree”.

Piloting and sample size calculation

We piloted the survey tool with 19 randomly selected medical students at the clinical school. Based on the post-piloting analysis, we found that 80% of the students owned smart devices giving a proportion of 0.8. We then refined the questionnaire before using it for survey with 169 first year clinical medical students. The refinement process involved removal of the question “brand of smart device owned”, and updated the list of mobile apps in the questionnaire after discovering new apps from the pilot process. The objectives of the study were explained verbally to these students and written consent was obtained before the survey. Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary and each student was allowed 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire anonymously. We determined the sample size needed for statistical significance with 95% confidence interval was 118 students. We conducted the survey on all 169 first year clinical medical students in the university from which 155 students responded, giving a response rate of 91.7%.

Statistical analysis

From the initial sample size of 155 students, we excluded the responses from 19 students from statistical analysis as these students did not own a smart device. In addition, we also excluded the responses from another 17 students from statistical analysis as these students did not have medical apps installed on their smart devices. Consequently, the responses from 119 students who owned and had medical apps installed on their smart devices were used for statistical analysis.

We analysed the data using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20 for Windows 7. Descriptive analysis was performed to delineate the demographic data. To determine statistical significance, comparison of mean using the one sample student-t test was done. For the purpose of analysis, a test value of 3 (unsure) was assigned as the test value. Mean values above the test value was considered as agreeing to the question statement while mean values below the test value was considered as disagreeing to the question statement. All p values were ‘two tailed’ with 95% confidence interval with p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the International Medical University and was registered with the National Medical Research Register of Malaysia.

Results

Demographics

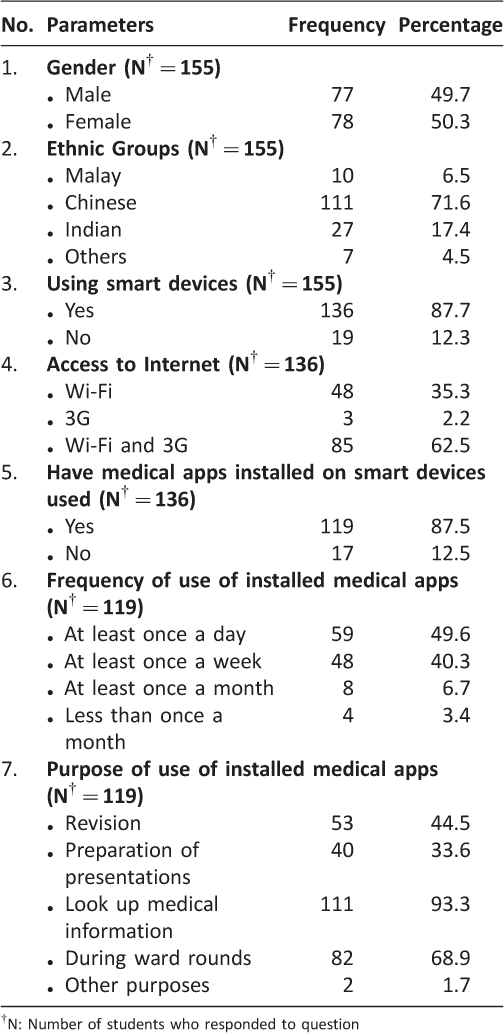

In total, 155 students participated in the study. The male to female ratio was almost equal. The majority of the students were of Chinese ethnicity (71.6%), followed by Indians (17.4%), Malays (6.5%) and other ethnicity (4.5%). Of the respondents, 136 (87.7%) of them owned at least one smart device, with a majority of their devices equipped with both Wi-Fi and 3G (62.3%) capabilities. Only 35.3% of them had just Wi-Fi function while 2.2% had just 3G access on their smart devices. One hundred and nineteen of the 136 students (87.5%) had medical apps installed on their smart devices. About 50% of them used them at least once a day, and 40% used them at least once a week. Most of the respondents used the medical apps to look up medical information (93.3%), during ward rounds (68.9%) and during revision (44.5%). The details of student population, frequency and purpose of medical apps usage are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic data of medical students

Medical apps

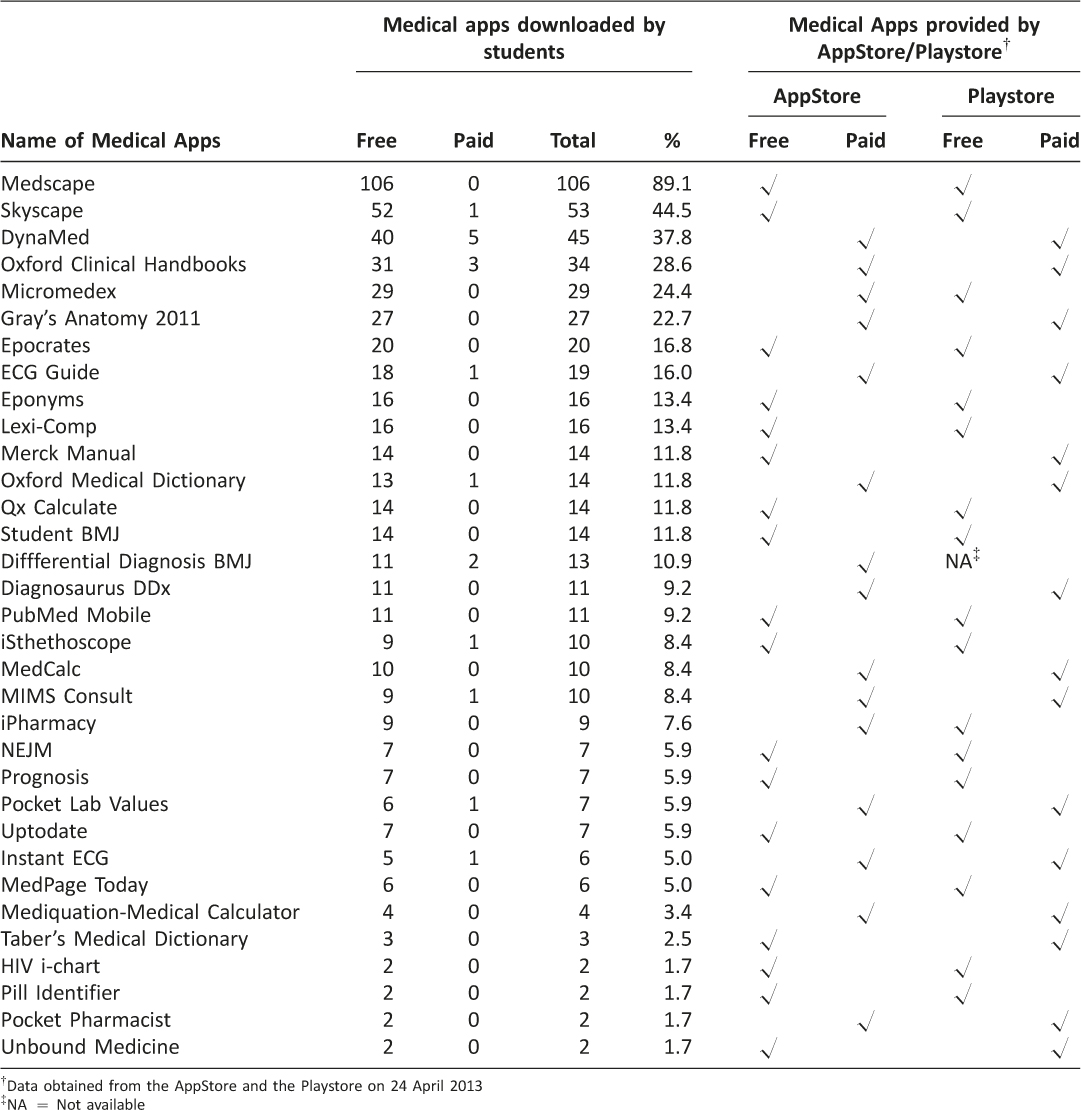

We found that the students downloaded their medical apps mainly from the AppStore (for iOS users) and Playstore (for Android users). The ratings of these apps ranged from 3.5 to 5, with a maximum of 5. The top 3 most popular medical apps downloaded were Medscape (89.1%), Skyscape (44.5%) and DynaMed (37.8%). Free apps were preferred over paid apps. The details of the medical apps downloaded by the respondents are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Details and types of medical applications downloaded by medical students in order of frequency

Medical students’ perception regarding medical apps

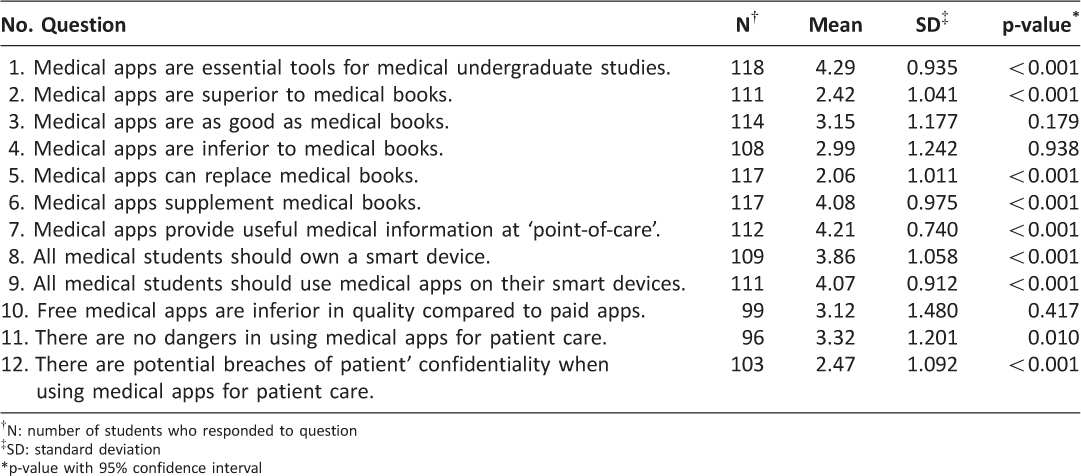

We found most medical students perceived medical apps as essential tools for medical undergraduate studies and felt that all medical students should own a smart device and use medical apps installed on their devices (p < 0.001). They perceived that medical apps can supplement medical books (p < 0.001) and provide useful medical information at ‘point-of-care’ (p < 0.001) although they disagreed that medical apps are superior to, or can replace medical books (both p < 0.001). They appeared to be ambivalent whether medical apps are as good as or inferior to medical textbooks (p = 0.179 and 0.939, respectively). The students perceived that free medical apps are inferior in quality compared to paid apps although this was not statistically significant (p = 0.417). The students disagreed that there is potential for compromise of patient confidentiality when using medical apps for patient care (p < 0.001) although they recognized that there may be potential danger in using medical apps (p = 0.010). The details are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Students’ perceptions related to medical apps

Medical students’ perception on the impact of medical apps on clinical practice

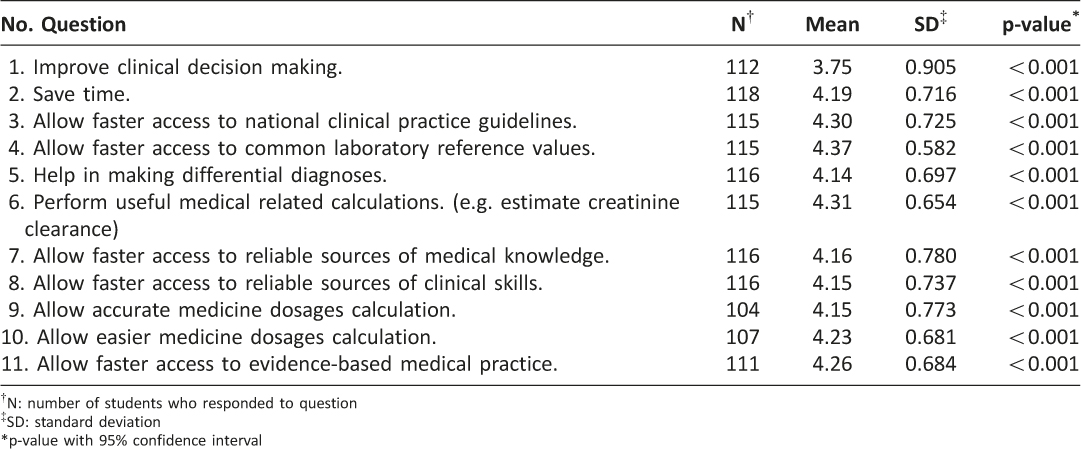

Medical apps were perceived by medical students to helped improve their clinical decision making, saved time, allowed faster access to national clinical practice guidelines, allowed faster access to common laboratory reference values, helped in making differential diagnoses, enabled useful medical related calculations, allowed faster access to reliable sources of medical knowledge, allowed faster access to reliable sources of clinical skills, allowed accurate medicine dosages calculation, allowed easier medicine dosages calculation and allowed faster access to evidence-based medical practice (p < 0.001). The details are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Students’ perception on the impact of medical apps on clinical practice

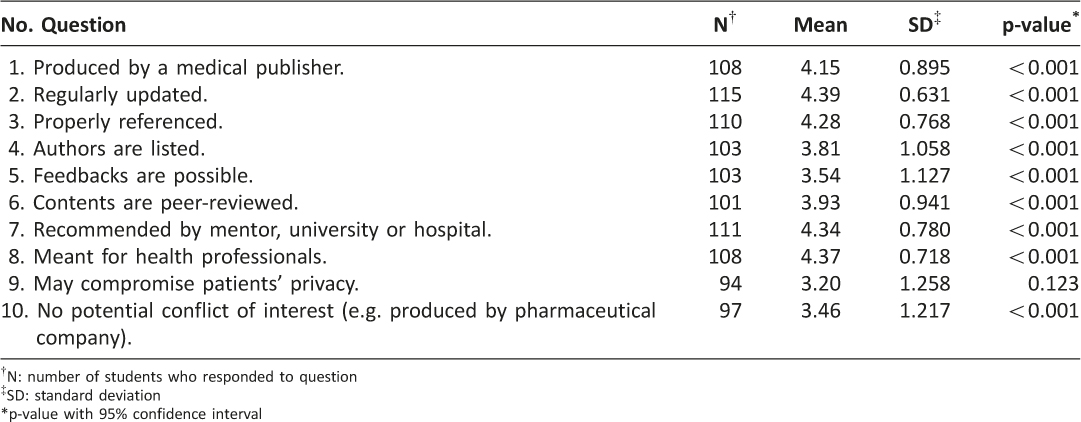

Medical students’ perception about the characteristics of an ideal medical app

The respondents generally agreed on almost all of the characteristics listed in the questionnaire that an ideal medical app should possess except for one (Table 5). They agreed that an ideal medical app should be produced by a medical publisher, regularly updated, properly referenced, authors are listed, feedbacks are possible, contents are peer-reviewed, recommended by mentor, university or hospital, is meant for health professionals, and has no potential conflict of interest (p < 0.001). The one criteria which the students did not consider to be an important criteria in an ideal medical app is the potential compromise of patient privacy (p = 0.098).

Table 5: Students’ perception on the characteristics of an ideal medical app.

Discussion

The majority of first year clinical medical students from IMU owned a smart device but not all had medical apps installed in their smart devices. In this study, we found that the prevalence of medical students who owned a smart device was 87.7%, which was higher than the finding of other similar surveys which showed 79% and 77% in the United Kingdom and Australia, respectively.12,13 Our study also showed the prevalence of medical students who owned smart devices with installed medical apps on their devices was 87.5%. These findings may suggest that it is a global trend and practice for medical students to own a smart device and use medical apps to support their study and clinical sessions. Most well known medical schools in United States and United Kingdom use this new technology in their medical curriculum, with the ultimate goal that once medical students graduate, they will be ready to join the rank of nearly 80% of physicians who use smart phones in their medical practice.6,14,15

We found that 93.3% of medical students used medical apps to look up medical information and 68.9% of them used these medical apps during ward rounds. The majority of them had positive perceptions on medical apps usage believing that medical apps were essential tools for undergraduate studies, allowing for faster, easier and reliable access to clinical guidelines, knowledge and skill as well as helping in decision making and formulating differential diagnoses. They also found medical apps to be useful for performing accurate medical related calculations and drug dosages. Several studies performed in the United Kingdom and Australia among medical faculty staff and medical students showed similar positive attitude towards medical apps usage in clinical practice.15,16

In comparison to medical books, medical students appeared uncertain if medical apps were as good as or inferior to medical books. The reason for this uncertainty may be due to the different geo-locations of these students during different times of the day. When these medical students are on the move or are in attendance at clinical sessions in the hospital, most of them would prefer medical apps, given that smart devices especially smart phones or tablets are very convenient and handy compared to relatively bulky textbooks. On the other hand, most of these medical students would probably prefer the traditional way of study using textbooks when they are at home or are in the library.

Interestingly, we found that the medical students in this study appeared unconcerned that the use of medical apps may potentially compromise patient confidentiality nor did they consider the issue of potential leak of patient’s data to be an important criteria of an ‘ideal medical app’ although several studies have highlighted the potential dangers with regards to the use of smart devices and potential breach of patient privacy and confidentiality.11, 17 The apparent lack of concern may be because the apps used by these students largely contained medical information or references rather than apps which are used directly in the management of patients with capability of transmitting sensitive data over the internet. Nevertheless, efforts should be made to address this apparent apathy among medical students to raise their awareness of the potential perils of using medical apps as well as to train them to use medical apps judiciously and wisely.

Limitations

This study only assessed the prevalence of smart devices ownership and medical apps usage among first year clinical medical students and their perceptions on the impact of medical apps on their clinical practice. The perceptions among more senior medical students may change as they gain more knowledge and insight in medicine. Most of the medical apps downloaded by the students in our study fell mainly in the non-surgical domain of medicine and therefore their impact on surgical practice could not be readily assessed. In addition, the impact on clinical practice by the use of medical apps were assessed through the perception of medical students in our study which may be influenced by factors such as differing level of clinical competence of these students and individual preferences or bias. Future studies may be done using more quantitative methods of assessment including the direct observation of clinical practice of the students by content experts and formal audit of clinical competencies in students using medical apps.

Conclusion

There is a high uptake and usage of smart devices and medical apps amongst first year clinical medical students with positive perceptions towards their use and impact on clinical practice. Medical schools should encourage the use of and medical apps among medical students whilst having strategies in place to safeguard patient confidentiality.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding/Support

Research Grant Project ID No. CSc/Sem6(01)2012, International Medical University.

Other disclosures

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: all authors had financial support from the International Medical University for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval

The Research and Ethics committee of the International Medical University approved this survey instrument and protocol prior to distribution.

References

1. Boulos MNK, Wheeler S, Tavares C, et al. How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: an overview. BioMed Eng OnLine 2011;10:24. ![]()

2. Ahmed B. There will be more than 13,000 medical apps in 2012 in Apple Appstore. Medicalopedia Mac 12, 2012. www.medicalopedia.org/1509/13000-medical-apps-2012-apple-appstore (accessed 6 June 2013).

3. Robinson T, Cronin T, Ibrahim H, et al. Smartphone use and acceptability among clinical medical students: a questionnaire-based study. J Med Syst 2013;37:9936.

4. Epocrates invests in future physicians. http://globenewswire.com/news-release/2012/08/17/483115/10002303/en/Epocrates-Invests-in-Future-Physicians.html (accessed 27 September 2013).

5. What smartphone apps are medical students using? Doctors in Training. http://www.doctorsintraining.com/blog/what-smartphone-apps-are-medical-students-using/ (accessed 27 September 2013).

6. Manhattan Research. Smart phones, Tablets and Mobile Marketing. http://manhattanresearch.com/Research-Topics/Healthcare-Professional/Mobile (accessed 1 August 2013).

7. Stanford School of Medicine. http://med.stanford.edu/estudent/ipads/app-recommendations.html (accessed 27 September 2013).

8. Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. http://msg.med.upenn.edu/?p=17784 (accessed 27 September 2013).

9. Top five medical apps at Harvard Medical School. http://mobihealthnews.com/10745/top-five-medical-apps-at-harvard-medical-school/ (accessed 27 September 2013).

10. University of Minnesota. http://www.meded.umn.edu/students/ipad_apps.php (accessed 27 September 2013).

11. Visser BJ, Bouman J. There’s a medical app for that. BMJ Careers April 18, 2012. http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20007104 (accessed 11 June 2013).

12. Payne KFB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related App use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121. ![]()

13. Koehler H, Yao K, Vujovic O, et al. Medical students’ use of and attitudes towards medical applications. Journal Mob Technol Med 2013;1:4,16–21.

14. Medical App Journal. Apps for Med Students- Impact on Medical Education. Medical App Journal September 12, 2012. http://medicalappjournal.com/medicalblog/2012/09/12/medical-mobile-apps-for-medical-students/ (accessed 7 July 2013).

15. Koehler N, Vujovic O, McMenamin C. Healthcare professionals’ use of mobile phones and the internet in clinical practice. Journal Mob Technol Med 2013;2(1):3–12. ![]()

16. Aungst T. Survey results show how medical student use of medical apps differs from resident physicians. iMedicalapps April 25, 2013. http://www.imedical apps.com/2013/04/survey-medical-student-medical-app-resident-physician/ (accessed 21 August 2013).

17. Gilhooly K. Growing use of smartphones and tablets may compromise patient privacy. Plastic Surgery Education Network July 23, 2012. http://www.psene twork.org/News/Detail.aspx?cid=aa423aea-cf6f-4a1f-9a3e-0b52f1655500 (accessed 21 August 2013).