“mHealth is an Innovative Approach to Address Health Literacy and Improve Patient-Physician Communication – An HIV Testing Exemplar”

Disha Kumar1,2, Monisha Arya, M.D., M.P.H3,4

1School of Social Sciences, Rice University, 6100 Main St., Houston, Texas 77005, U.S.A; 2Wiess School of Natural Sciences, Rice University, 6100 Main St., Houston, Texas 77005, U.S.A; 3Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases and Section of Health Services Research, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030, U.S.A; 4Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center 2002 Holcombe Blvd (Mailstop 152), Houston, Texas 77030, U.S.A

Corresponding Author: disha.kumar@ricealumni.net

Journal MTM 4:1:25–30, 2015

Low health literacy is a barrier for many patients in the U.S. Patients with low health literacy have poor communication with their physicians, and thus face worse health outcomes. Several government agencies have highlighted strategies for improving and overcoming low health literacy. Mobile phone technology could be leveraged to implement these strategies to improve communication between patients and their physicians. Text messaging, in particular, is a simple and interactive platform that may be ideal for patients with low health literacy. We provide an exemplar for improving patient-physician communication and increasing HIV testing through a text message intervention.

Low health literacy leads to poor patient-physician communication and worse health outcomes

Health literacy is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”1 According to the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, over 36% and 14% of U.S. adults have below intermediate and below basic health literacy, respectively.2 Racial and ethnic minorities are most impacted by low health literacy, with 41% of Hispanics and 24% of African-Americans having below basic health literacy.2 Patients with low health literacy make less use of preventive healthcare services3,4 and suffer worse health outcomes.5,6 Moreover, as noted by the American Medical Association, patients with poor health literacy have poor communication with their physicians, leading to poor health outcomes.7 Interventions aimed at improving patient-physician communication positively correlate with improved health.8

Mobile health could improve patient-physician communication

As noted by former U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary, Kathleen Sebelius, in her keynote address at the annual Mobile Health (mHealth) Summit, mobile technologies are “opening up new lines of communication between patients and their physicians” and are an innovative strategy to engage traditionally hard-to-reach populations such as racial and ethnic minority communities.9 mHealth could be an innovative way to overcome health literacy barriers because of its reach: mobile phone ownership is ubiquitous across race, ethnicity, education, and income levels.10,11 The Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Health Literacy’s Collaborative on New Technologies highlighted how the ubiquity of mobile phones is closing the digital divide faced by many low health literacy patients.12 mHealth offers potential to engage patients with low health literacy by conveniently delivering relevant health information that could improve patient-physician communication.

Text messaging is the most common activity performed on a mobile phone, with 81% of mobile phone owners sending and receiving text messages.11 Thus, text messaging is an ideal platform for delivering health interventions to patients. Studies have found that text messages have been successful at promoting patient-physician communication,13 smoking cessation,14,15 weight loss,16,17 and immunization coverage.18 This may be because text messages have several salient health promotion features, especially beneficial for low health literacy patients. mHealth text messages can be: 1) written in simple text, 2) personalized based on the patient’s health literacy level, and 3) interactive to facilitate communication between patient and physician. Based on these many aspects, text message interventions hold great potential to engage patients and improve communication between patients and physicians.

Adopting text messages to empower patients with low health literacy

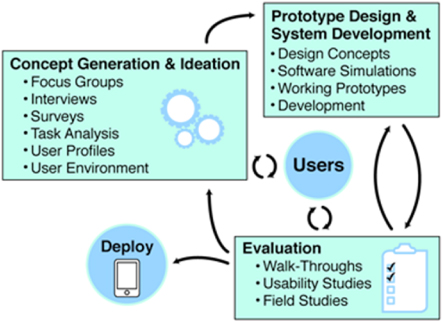

Government agencies have highlighted the importance of designing health interventions that are appropriate for patients with low health literacy. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Quick Guide to Health Literacy recommends using health literacy strategies, such as improving the usability of and access to health information.19 Additionally, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit recommends using patient feedback to evaluate the usability of the health information presented.20 Finally, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy emphasizes targeting and tailoring communication in health interventions and the use of User-Centered Design (UCD).21 UCD employs strategies for end-users to influence iterative prototypes of a product (Figure 1).22,23 Although UCD strategies are generally employed in products more complex than text messaging, UCD offers valuable insight to ensure text messages result in increased patient-physician communication, and positive and sustained health engagement.

Figure 1: The User-Centered Design Process23 (Adapted from McCurdie et. al)

Challenges to note in developing a text message intervention

Certain challenges may exist in text message interventions; however, these challenges can be addressed if they are identified early in campaign development. First, although text messaging transcends race, ethnicity, education, and income levels,11 text messaging is not pervasive among the elderly. Compared to over 94% of adults 18-49 years who own a cell phone use text messaging, only 35% of adults over 65 years who own a cell phone use text messaging.11 However, older adults are increasingly using text messaging. In 2013, 35% of adults 65 years or older used text messaging, compared to only 11% of adults in this age group in 2009.24 Based on current trends, mHealth interventions targeting older adults may be better suited for these end-users as their familiarity with text messaging increases. Second, the privacy and security of patient information sent over text message should comply with local and national regulations (e.g. the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996). Additional research is needed to identify risks associated with text messaging;25 updated security measures and regulations may need to be implemented.26 Third, it is important to note that text messages are limited to 160 characters. While text messages can effectively reach target audiences, the campaign message must be succinct enough to convey the intended information. Similarly, costs may be incurred by the end-user in receiving text messages. However, one in three U.S. adults have unlimited text plans, limiting the patients who will have to bear a cost burden.27 Finally, mHealth interventions may not always improve health to the full expectations of the campaign designers. For instance, Sweet Talk, a text message system that supported adolescents with diabetes, did not improve glycemic control.28 However, the system improved additional goals of the campaign: diabetes self-efficacy and self-management.28 Despite these limitations, strategic text message campaigns have been successfully implemented internationally and could be used as a model.13–18,29,30 Text message campaign designers should be flexible and aware of the abilities and preferences of the target audiences.

Exemplar: Text messaging could engage patients and increase HIV testing

The HIV epidemic continues in the U.S. as approximately 50,000 persons contract HIV each year.31 HIV disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities. Despite national recommendations for routine HIV testing,32,33 several reports highlight that physicians are not recommending HIV testing to their patients – even those at highest risk for HIV.34–38 Interestingly, patients want and expect HIV testing to be done and want their physician to test them.39 Conversely, physicians want their patients to ask them for the HIV test.40

Health literacy impacts HIV health disparities.41 Low health literacy and poor patient-physician communication are associated with poorer HIV knowledge.42 Low health literacy may be a contributing factor to low HIV testing rates, particularly among the racial and ethnic minority communities hardest hit by the HIV epidemic. Because studies have found that text messages can promote patient-physician communication,13 HIV informational text messages could motivate patients to ask their physicians about the HIV test. This intervention could thereby increase patient-physician communication and HIV testing. A study of predominately African-American patients found that 77% of them felt they could be convinced by a text message to get HIV tested.43 Unlike static HIV testing campaigns, such as those on billboards, HIV text message interventions could be sent near the time of patients’ appointments with their physicians. Targeted text messages could revolutionize preventive health practices, such as HIV testing, by facilitating communication between low health literacy patients and their physicians.

Conclusion

As highlighted in the Institute of Medicine report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion, the health system has significant opportunity and responsibility to improve health literacy.44 The health system should capitalise on the potential of mHealth to engage people in their health and overcome some of the barriers faced by patients of low health literacy. Despite the proven positive effects that mHealth campaigns have had on health behaviors,13,45,46 mHealth as a patient-empowerment tool remains in its infancy. More research is needed on the ability of mHealth to improve health for the hardest-to-reach populations, such as those with low health literacy. Successful mHealth strategies should incorporate health literacy strategies19–21 and user-centered design.21,23 Prompting patients with a simple health message before their physician appointment could motivate patients to talk to their physician about a pertinent health issue, thus overcoming low health literacy barriers. Utilizing mHealth specifically for HIV testing, as in the exemplar provided, could achieve several Healthy People 2020 objectives: improve patient-physician communication, improve HIV testing, and increase use of mHealth.47

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Rice University Janus Award (Disha Kumar), an undergraduate research scholarship, and by a National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health K23 grant (MH094235-01A1, PI: Arya). This work was supported in part by the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413), Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or Rice University. We have no conflict of interests to disclose.

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: D. Kumar reports stipend from Rice University, M. Arya reports grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

This paper or papers similar to it have not been published previously by any of the authors.

The authors wish to thank Ms. Sajani Patel and Ms. Anna Huang for their thoughtful comments and editorial assistance on the manuscript.

References

1. Parker RM, Ratzan SC. National library of medicine current bibliographies in medicine: health literacy. National Institutes of Health (U.S.); 2000. (Accessed Oct 29, 2014, at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20061214/pubs/cbm/hliteracy.html#15.)

2. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, White S. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. U.S. Department of Education, 2006. (Accessed June 19, 2014, at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf.)

3. Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Medical care 2002;40:395–404.

4. Fortenberry JD, McFarlane MM, Hennessy M, et al. Relation of health literacy to gonorrhoea related care. Sexually transmitted infections 2001;77:206–11.

5. Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of general internal medicine 2004;19:1228–39.

6. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of internal medicine 2011;155:97–107.

7. Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 1999;281:552–7.

8. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 1995;152:1423–33.

9. Sebelius K. mHealth Summit Keynote Address. 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (Accessed Oct 25, 2014, at http://www.hhs.gov/secretary/about/speeches/2011/sp20111205.html.)

10. Pew Research Center. Mobile Technology Fact Sheet. (Accessed June 19, 2014, at http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/.)

11. Duggan M. Cell Phone Activities 2013. Pew Research Center. (Accessed May 17, 2014, at http://pewinternet.org/–/media//Files/Reports/2013/PIP_Cell%20Phone%20Activities%20May%202013.pdf.)

12. Broderick J, Devine T, Langhans E, Lemerise AJ, Lier S, Harris L. Designing Health Literate Mobile Apps. Institute of Medicine, 2014. (Accessed June 20, 2014, at http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2014/Discussion-Papers/BPH-HealthLiterateApps.pdf.)

13. Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiologic reviews 2010;32:56–69.

14. Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, et al. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tobacco control 2005;14:255–61.

15. Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:49–55.

16. Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, et al. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2009;11:e1.

17. Steinberg DM, Levine EL, Askew S, Foley P, Bennett GG. Daily text messaging for weight control among racial and ethnic minority women: randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of medical Internet research 2013;15:e244.

18. Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, et al. Text4Health: impact of text message reminder-recalls for pediatric and adolescent immunizations. American journal of public health 2012;102:e15–21.

19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Disease Prevention and Promotion. Quick Guide to Health Literacy. 2008. (Accessed June 20, 2014, at http://www.health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/Quickguide.pdf.)

20. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. 2010. (Accessed June 20, 2014, at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthliteracytoolkit.pdf.)

21. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Disease Prevention and Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. 2010. (Accessed June 20, 2014, at http://www.health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Lit_Action_Plan_Summary.pdf.)

22. Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D. J. P. User-Centered Design. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction 2004.

23. McCurdie T, Taneva S, Casselman M, et al. mHealth consumer apps: the case for user-centered design. Biomedical instrumentation & technology / Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation 2012;Suppl:49–56.

24. Taylor P, Morin R, Parker K, Cohn D, Wang W. Growing Old In America: Expectations vs. Reality. 2009. (Accessed 2 Oct, 2014, at http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/Getting-Old-in-America.pdf.)

25. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Text4Health Task Force. Health Text Messaging: HHS Text4Health Task Force Recommendations. (Accessed 23 Oct 2014, at http://www.hhs.gov/open/initiatives/mhealth/recommendations.html.)

26. United States Government Accountability Office. Information Security: Better Implementation of Controls for Mobile Devices Should Be Encouraged 2012. GAO-12-757. (Accessed 24 Oct 2014, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/650/648519.pdf.)

27. Tumminello M. Don’t Lose Your Voice – The Flipside of Cell Phone Statistics. 2013. (Accessed 2 Oct 2014, at http://www.televox.com/blog/patientcommunication/dont-lose-your-voice-the-flipside-ofcell-phone-statistics/.)

28. Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a textmessaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabetic medicine: a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2006;23:1332–8.

29. Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS 2011;25:825–34.

30. Bourne C, Knight V, Guy R, Wand H, Lu H, McNulty A. Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection/HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted infections 2011;87:229–31.

31. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS in America: A Snapshot. 2014. (Accessed Oct 24, 2014, at www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/HIV-and-AIDS-in-America-A-Snapshot-508.pdf.)

32. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe AM, et al. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:1–17.

33. Moyer VA. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of internal medicine 2013;159:51–60.

34. Kim EK, Thorpe L, Myers JE, Nash D. Healthcarerelated correlates of recent HIV testing in New York City. Preventive Medicine 2012;54:440–3.

35. Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, Samet JH. Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. Journal of general internal medicine 2004;19:349–56.

36. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection–South Carolina, 1997–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:1269–72.

37. Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS patient care and STDs 2011;25:657–64.

38. Chin T, Hicks C, Samsa G, McKellar M. Diagnosing HIV Infection in Primary Care Settings: Missed Opportunities. AIDS patient care and STDs 2013;27:392–7.

39. McAfee L, Tung C, Espinosa-Silva Y, et al. A survey of a small sample of emergency department and admitted patients asking whether they expect to be tested for HIV routinely. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care 2013;12:247–52.

40. White BL, Walsh J, Rayasam S, Pathman DE, Adimora AA, Golin CE. What Makes Me Screen for HIV? Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Conducting Recommended Routine HIV Testing among Primary Care Physicians in the Southeastern United States. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care 2014. ![]()

41. Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Health literacy: an overlooked factor in understanding HIV health disparities. American journal of preventive medicine 2007;33:374–8.

42. Kalichman SC, Benotsch E, Suarez T, Catz S, Miller J, Rompa D. Health literacy and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDS. American journal of preventive medicine 2000;18:325–31.

43. Arya M, Kallen MA, Street RL, Jr., Viswanath K, Giordano TP. African American Patients’ Preferences for a Health Center Campaign Promoting HIV Testing: An Exploratory Study and Future Directions. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care 2014. ![]()

44. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy; Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004: 35.

45. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS medicine 2013;10:e1001362.

46. Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. American journal of preventive medicine 2009;36:165–73.

47. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives. (Accessed May 17, 2014, at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/TopicsObjectives2020/default.aspx.)