Perceptions of Using Smartphone Technology for Dietary Assessment among Low-Income African-American Mothers

Nuananong Seal, Ph.D., RN1, Oluwatoyin Olukotun, BSN, RN1

1University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Correspondence Author: nseal@uwm.edu

Journal MTM 4:2:12–20, 2015

Background: Smartphone technology is the fastest growing in U.S. populations particularly in African -American community. Smartphone technology, therefore, may hold promise for improving health communication and accuracy of dietary intake assessment in this population. There is no information about maternal perceptions of using smartphone for dietary assessment. This paper reports the perceptions of low-income African -American mothers of children aged four to five years towards the use of smartphone for their children’s dietary intake assessment and as a means of receiving nutritional feedback.

Methods: A total of 17 low-income African -American mothers, who attended a large food pantry community center in Wisconsin and were eligible to participate in the study, completed either focus group discussions or individual interviews. The mothers also completed a self-administered demographic and smartphone activity patterns survey. The mothers who were interested in taking a photograph of a meal of their child were provided a private email address for sending the photographs to the researcher using their smartphones.

Results: The focus group and interview data were analyzed using thematic and structural analysis techniques. Mothers’ mean age was 37 years (range 23-48 years) with mean BMI at 33 (range 23-40). Children’s mean age was 4.8 years (range 4-5.6 years). Children’s mean BMI percentile was at the 92nd percentile (range 82nd – 96th percentile). These mothers seemed to have favorable attitudes towards the use of smartphones to take photographs of their children’s diets and receive nutritional feedback for their children.

Conclusion: The mothers in this study have a strong interest in using their smartphones to assess their children’s diets and download mobile health apps i.e. healthy recipes, and receive nutritional feedback for their children’s diets via SMS. Smartphone technology appears to hold great potential in terms of accurate, efficient, user-friendly, and flexible features in helping these low-income African-American mothers and health care providers to assess children’s dietary intake. Further studies testing the acceptability of mobile-based health apps in low-income African-American mothers and its effects on their children’s healthy body weight and nutritional well-being are warranted.

Introduction

Childhood obesity remains a public health concern and requires considerable attention from all stakeholders including policy makers, healthcare providers, schools, teachers and families. Childhood obesity is defined as a body mass index percentile (BMI%) ≥ 95% and overweight as BMI% ≥ 85% for age and gender.1 As of 2011-2012, 17% of US children from 2- to 19- year olds were obese.2 While the rates of childhood obesity in the general population are high, they are even higher in low income African -American population.3 African -American girls have the highest rates of obesity and the leading rate of increase in obesity from 16.3% in 1994 to 29.2% in 2007-2008, compared with all other racial/ethnic subgroups.3 Overweight children are at increased risk for multiple health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.4 Equally disturbing health risks for overweight children include poor self-esteem and depression due to social discrimination.4

Obesity rate among African -American children tends to be higher than other ethnic groups and has increased more rapidly over time.5 The current high rates of obesity among young children in the U.S. are primarily a result of maternal feeding practices and environmental factors that lead to excess caloric intake.6 Few preschoolers met the guidelines for food energy, vegetables and fruits, and the numbers are even lower for African American children.7 Nevertheless, information related to the quantity and quality of food intake in African -American children has not been fully elucidated. This brings in some challenges against obesity prevention in these children. Potential factors that impact food intake and weight status in African -American children include limited knowledge of healthy eating and misperception of child’s weight status in their parents.7

Information about children’s dietary intake is essential in helping parents and primary care providers develop a plan or strategy to prevent obesity and maintain healthy weight in children since obesity has a strong association with nutritional components.7 There are several methods used for dietary intake assessment such as a 3-day food record survey and food frequency questionnaires. However, these assessment methods have some disadvantages including underreporting or incomplete reporting due to memory dependent or subject to bias and time consuming.8 Smartphones have a variety of advantages technological features i.e., built-in camera which can further prompt the enhancement of dietary assessment, improve accuracy of dietary assessment and decrease time spent. National data in 2011 showed that one-third of the smartphone users were low-income families and 49% of smartphone owners were African Americans.9,10 Given that smartphone technology is the fastest growing in U.S. populations particularly in African -American community, smartphone technology may hold promise for improving health communication and accuracy of dietary intake assessment in this population. Short message service (SMS) available in a smartphone offers a low-cost and relatively discreet method for strengthening information exchange.

To the best of our knowledge there is no information about maternal perceptions of using smartphone for dietary assessment. This paper is the first to report the perceptions of low-income African -American mothers of young children towards their use of smartphone to assess dietary intake of their children and as a means of receiving nutritional feedback. Given the popularity of smartphone users, it was hypothesized that individuals would have favorable attitudes towards the use of smartphone to take photographs of their children’s diets and receive nutritional feedback via SMS.

Methods

Qualitative methods using two focus-group interview discussions with ten African- American mothers were conducted in a private meeting room at a large food pantry community center in Wisconsin. Another seven mothers who volunteered to participate but unable to come to the focus groups were interviewed individually. After obtaining approval from the University Institutional Review Board and a written agreement from the Center, the recruitment flyers outlining the purposes of the study, study protocol, eligibility requirements for participants, and contact information of the investigators were distributed to women who attended the Center by a trained research assistant. Eligible individuals include 1) being African American and having a child aged between four and five years; 2) mainly be responsible in food preparation for their child; and 3) owning a smartphone with camera and data capabilities. This age group is selected because obesity appears to be more prevalent in children aged four and five than younger children.3 A major factor contributing to excess weight gain among this age group is food intake and mothers are a key food provider and role models for these children.6,11,12

Data Collection

Similar structured open-ended questions were used in the focus groups and individuals. Each mother provided written consent before participating in the session and was given a $20 gift card to compensate for her time. The mothers were asked to talk about dietary patterns of their child and their perceptions of using smartphone to assess dietary intake of their child and as a means of receiving information about their child’s nutrition. The session lasted approximately 60 minutes and was audio recorded. Following the discussion session, information on maternal age, education, marital status, income, prior experience of sending and receiving text messages, and patterns in smartphone activity were surveyed via a self-administered questionnaire. Child’s age, gender and BMI were also collected in the survey. After completion of the survey, the researcher asked mothers to voluntarily take a photograph of their children’s meal and send the photographs to the researcher using their smartphone. The mothers were assigned a private email address for sending the photographs. All mothers were given a grid placemat, developed by the researcher- Seal, to be used when taking photographs of their children’s meal. Figure 1 presents the photographs of the meals on a grid placemat of those volunteers’ children at before and after consumption. Figure 2 presents the photographs of the meals without a grid placemat.

Figure 1: Photographs of the meals on a grid placemat

Figure 2: Photographs of the meals without a grid placemat

Data Analysis

Interviewed data were professionally transcribed and coded. The data were then analyzed using thematic and structural analysis techniques. The data were coded and categorized independently by three project team members and the themes developed were compared to enhance the credibility of the results. Where there was disagreement, discussions were held to reach consensus. Naturalistic inquiry trustworthiness was established with evidence in an audit trail.13 The audit trail included documentation of the research process, transcriptions of the narratives generated, and reflective notes made during the discussions. The survey data were calculated using IBM SPSS® Statistics Version20. Descriptive statistics of frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations were calculated.

Results

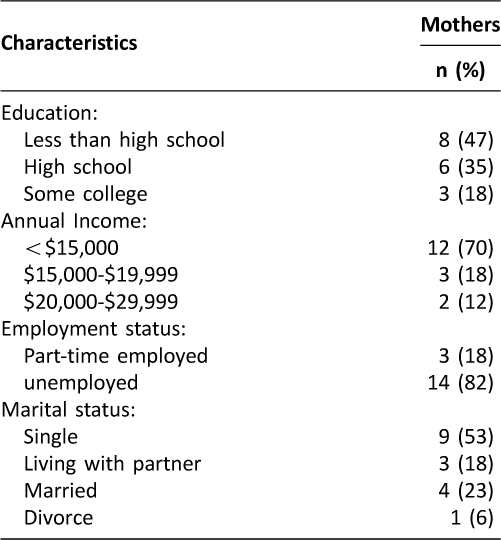

A total of 17 mothers participated in the study. Mothers’ mean age was 37 years (range 23-48 years) with mean BMI at 33 (range 23-40). Most mothers (70%) reported a household income less than $15,000/year, 82% were unemployed and 53% were single mothers. Mothers had an average of 2.5 children. Table 1 presents maternal characteristics. Children’s mean age was 4.8 years (range 4-5.6 years) and most of them were girls (68%). Children’s mean BMI percentile (calculated from maternal report of their children’s weight and height) was at the 92nd percentile (range 82nd – 96th percentile).

Table 1: Maternal Characteristics (N = 17)

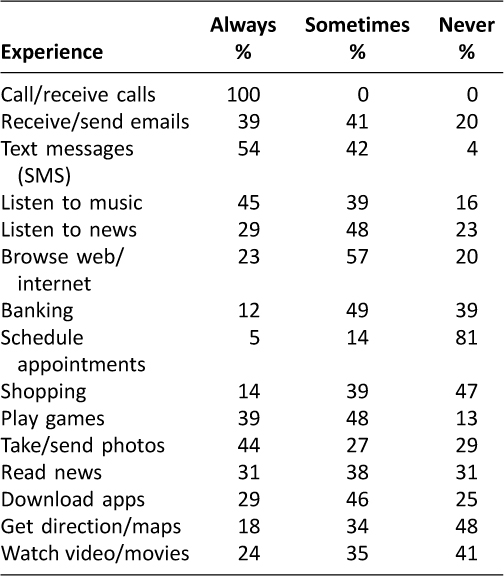

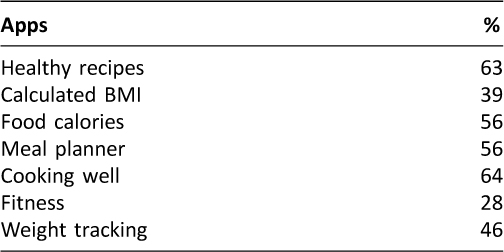

Data regarding maternal experience in smartphone activity patterns were present in Table 2. The common smartphone activities used by this group of mothers in addition to making and receiving calls (100%) were texting (89%), playing games (87%), and listening to music (84%). In addition, 71% of the mothers used their smartphone to take photographs and send them to their relatives and friends. The least popular smartphone activity in this group of mother was using smartphone to schedule appointment (19%). Seventy-five percent of the mothers reported that they downloaded health applications to their phones. Cooking and healthy recipes were the most downloaded apps by this group of mothers (64% and 63% respectively, see Table 3). Some mothers indicated their interest in mobile-based health advisor or health coaching. The most concern with regard to downloading of mobile-based health apps among these mothers was the cost for app downloads and user’s security such as hacking. Most mothers (58%) had service plans with unlimited text and data.

Table 2: Smartphone activity patterns

Table 3: Smartphone apps related to health information downloaded by mothers

The following section illustrates the findings from the focus group discussions and individual interviews. The responses obtained from the focus groups and individuals appear to be similar. There are four main themes emerged from analysis: 1) Mothers’ perceptions of using smartphone to take photos of their children’s dietary intake; 2) Mothers’ perceptions towards smartphone; 3) Mothers’ perceptions towards a receipt of nutritional feedback via smartphone; and 4) Mothers’ perceptions and myth regarding their children’s diets and obesity.

1) Mothers’ perceptions of using smartphone to take photos of their children’s dietary intake

Most mothers believed that smartphone was a useful tool and could do several tasks including taking photos of foods that their children ate. Some mothers said they took photos of their children while eating a meal at a restaurant or a fast food place during special occasions i.e., birthday or some holidays. Most of them felt that taking photos was an easy way to see what and how much foods their children ate. Some mothers showed their interest in learning more about taking a photo of their children’s food intake and estimating their children’s caloric intake from a smartphone as this method seemed to be new to them.

“I took a photo of my child while eating his sandwich at McDonald on his birthday and sent it to his grandma using my smartphone. I think taking photos was easy and convenient.”

“I think it is easier than writing down what you eat. Sometimes it is hard to spell things out. A photo can show you everything… it’s right there.”

“I agreed. I like the idea of taking photos of foods and learn how much calories they are. How much do you eat, too much or too little, etc. My phone can take many photos…you even can go back and look at them again.”

2) Mothers’ perceptions towards smartphone

Most mothers felt that smartphone was associated with their routine and lifestyle although some mothers had a concern about cost and privacy of downloading smartphone apps.

“I need to have my smartphone with me. It helps me to connect to my loved one and someone I need to talk. I think it is part of my life”.

“I used to have a landline phone but not anymore. I don’t think I need it…smartphone is everything. I use it for everything these days.”

“I can’t think going out without my smartphone. When I need help the first thing I look for is my smartphone.”

“I use my smartphone to call, send SMS and sometimes browse internet and download stuff but I download only free ones. Some apps are expensive.”

“Sometimes I wanna download music or movie from my mobile but I got to give them my address, my email, phone number, etc… I don’t feel comfortable. I am afraid of being tracked and hacked.”

3) Mothers’ perceptions towards a receipt of nutritional feedback via smartphone

Most mothers stated that they kept their smartphone with them all the time. They also indicated that their smartphones had SMS features. Some mothers felt that getting feedback or comments on their children’s food intake via SMS would help them improve their children’s diets. Some mothers expressed that receiving feedback via SMS would be timeless and low cost. Mothers indicated that SMS was their preferred method of communication as it was quick, easy and inexpensive. Some mothers added that they would like to receive healthy recipes and real-time feedback via smartphone. One mother indicated that she would like to learn how to manage her child’s eating behavior via her smartphone.

“I sometimes can’t think of what food to cook for my children. Healthy recipes that I can store in my smartphone would be useful.”

“I never had real-time feedback from anyone sent to my smartphone. I would be interested to have feedback on my child’s diets sent to my phone.”

“My child takes long time to finish each meal. I wanted to learn how I could make him eat faster.”

4) Mothers’ perceptions and myth regarding their children’s diets and obesity

Mothers were asked to talk about their perceptions of children’s diets in relation to their health and obesity. Most mothers indicated that sweet foods could cause obesity. However, some mothers believed that sweet foods cause obesity in adults but not in children. Some mothers believed that pork products could cause high blood pressure and fatty meats cause diabetes. In addition, some mothers did not believe that juice and soda beverages could cause childhood obesity. Most mothers stated that they rarely drink water because they did not like the taste and neither did their children. Another mother stated that her children always drank milk, juice, and/or soda at home. When mothers were asked about how often the families ate vegetables and fruits, most of them said they had vegetables and fruits at least once a day and most were canned vegetables and fruits.

Most mothers felt that their children were big because they were growing. This group of mothers was more concerned about their children had not eaten enough food than had eaten too much foods. Some mothers expressed that they talked to their children to eat whatever given to them at schools so that they would not feel hungry. Some mothers said that they encouraged their children to empty their plates. Some used food as a way to reward their children.

“I would be telling him…don’t waste this. There are people in Africa who got nothing to eat… you have it and you need to eat it all.”

“I sometimes say to my child, you will get a cookie or ice cream if you finish your plate. He would be trying to empty.”

Discussion

The findings showed that these low-income African-American mothers seemed to have favorable attitudes towards the use of smartphone to take photographs of their children’s diets and receive nutritional feedback for their children. The mothers in this study indicated that smartphones were useful and associated with their routine and everyday lifestyle. Most mothers enjoyed taking photographs using their smartphones. They voluntarily sent the photographs of their children’s diets to the researcher via their smartphones (see Fig 1). In addition, most mothers expressed their interest in receiving real-time feedback for their children’s diets via SMS. More than 85% of the mothers already used their smartphones to send or receive text messages from family members and friends. National surveys revealed that minority parents including African Americans frequently communicate via mobile phone technology.14–16 The mothers’ perceptions of usefulness and ease of use of smartphones can lead to subsequent acceptance of mobile-based health interventions. Studies show that perceived usefulness and ease of use of information technology strongly predict users’ acceptance and intention to receive information or engage in mobile-based health interventions.17 Smartphones, therefore, hold great promise for reaching these low-income African -American mothers and providing them health interventions to support their children’s health. SMS is inexpensive and seems to be a feasible and acceptable method of communication and delivering nutritional feedback to the mothers in this study.

The mothers also indicated their interest in mobile-based health applications (apps) and 75% of them downloaded health apps such as healthy recipes to their smartphones. The findings are consistent with previous study that women appear to be taking the lead when it comes to smartphone technology use18,19 and download health apps.18 Studies show that African -American women are more likely than White ones to download apps and access health information on their phones.18,20 Smartphone apps allow users to receive resources for feedback and other information needs. However, cost of some smartphone apps and the user security and privacy issue can impact on the download behaviors of these mothers. Standards regarding user security and privacy must be upheld if we are to design a mobile-based health intervention and implementation.

The mothers in this study did not perceive their children as being overweight although their children’s mean BMI percentile was at the 92nd percentile. Instead the mothers felt that their children were big because they were growing. The findings demonstrated similar results to previous research. Low-income African -American mothers are more likely to underestimate their children’s body weight.21,22 A population-based study found that African -American mothers reported higher levels of restriction, pressure-to-eat, and monitoring of their child’s food intake compared to white mothers.23 These feeding practices can negatively influence their child’s eating behaviors and food intake; leading to overeating and obesity.24,25 Therefore, it is imperative to help parents change their feeding practices and their perceptions on child’s weight status and child’s eating behaviors. These low-income mothers have pervasive interest in mobile-based health information make it a promising platform for improving maternal feeding practices and reducing childhood obesity. More research targeting different socioeconomic and ethnic groups of mothers is recommended to find out their perceptions towards the use of smartphone and if any new themes are emerged from different populations.

Limitations

A few limitations need to be considered. This study was conducted in low-income African American mothers with children aged four and five years; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations of mothers from different socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds. In addition, the data with regards to body weight and height of the mothers and their children were from maternal self-report and that could be biased.

Conclusion

The study shows that these African -American mothers have a strong interest in using their smartphones to assess their children’s diets and download mobile health apps i.e. healthy recipes, and receive nutritional feedback for their children’s diets via SMS. Smartphone technology appears to hold great potential in terms of efficient, user-friendly, and flexible features in helping these African -American mothers and health care providers to assess children’s dietary intake. Technology features in smartphones have potential to enhance health communications and enable health care providers to deliver mobile-based health and nutrition interventions to improve maternal feeding practices and dietary management for their children. Further studies testing the acceptability of mobile-based health apps in low-income African -American mothers and its effects on their children’s healthy body weight and nutritional well-being are warranted.

Disclosure

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: funding support from University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, College of Nursing for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2002; 11(246). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf (access 29 Nov, 2013).

2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal K. M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Journal of the American Medical Association 2014;311(8):806–814. ![]()

3. Polhamus B, Dalenius K, Borland E, et al.. Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance 2007 Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/pednss/pdfs/PedNSS_2007_text_only.pdf (accessed 25 Nov 2013).

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and Obesity Health Consequences 2011. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/consequences.html

5. Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Rising social inequalities in US childhood obesity, 2003-2007. Annals of Epidemiology 2010a;20(1):40–52.

6. Coker TR, Chung PJ, Cowgill BO, et al. Low-Income Parents’ Views on the Redesign of Well-Child Care. Pediatrics 2009;124:194. doi:![]() .

.

7. Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutrition 2009;12:267–83. doi:![]() .

.

8. Burrows TL, Martin RJ, Collins CE. A systematic review of the validity of dietary assessment methods in children when compared with the method of doubly labeled water. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2010;110(10):1501–10. ![]()

9. Marketing Charts staff. Smartphone use. Retrieved from http://www.marketingcharts.com/online/african-american-smartphone-penetration-higher-19414 (accessed 19 Jun 2014).

10. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project January 20-February 19, 2012 tracking survey. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/Smartphone%20ownership%202012.pdf (accessed 25 Jul 2014)

11. Seal N, Seal J. Eating patterns of the rural families of overweight preschool children: A pilot study. Scientific International Journal, Journal of Education and Human Development 2009. http://www.scientificjournals.org/journals2009/articles/1436.pdf

12. Seal N. Using a mobile phone to assess dietary intake in young children. In M. Jordanova & F. Lievens, (eds.). Global Telemedicine and eHealth Updates: Knowledge Resources (2014, pp. 518–20). ISBN 1998-5509

13. Guba EG. Criteria for Assessing the Trustworthiness of Naturalistic Inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology 1981;29(2):75–91. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30219811 (accessed 19 Jun 2014).

14. Brenner J. Pew Internet: Mobile. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. Jun 06, [2013-07-12]. Retrieved from webcitehttp://pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/February/Pew-Internet-Mobile.aspx.

15. Fox S, Duggan M. Mobile Health 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2012. Nov 08, [2013-07-11]. Retrieved from webcitehttp://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_MobileHealth2012_FINAL.pdf (accessed 09 Jul 2014)

16. Duggan M, Rainie L. Cell Phone Activities 2012. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2012. Nov 25, [2013-07-12]. Retrieved from webcitehttp://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Cell-Activities.aspx (accessed 09 Jul 2014)

17. Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q 2003;27(3):425–78.

18. Oglivy Action, Women Taking the Lead When It Comes to Mobile, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/media-network/medianetwork-blog/2012/aug/06/women-lead-mobile-technologyretail.

19. Velez O. A Usability Study of a Mobile Health Application for Rural Ghanaian Midwives. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 2013;00:1–8.

20. Mitchell SJ, Godoy L, Shabazz K, Horn IB. Internet and Mobile Technology Use Among Urban African American Parents: Survey Study of a Clinical Population. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2014;16(1):e9. ![]()

21. Baughcum AE, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, et al. Maternal perception of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics 2000;106(6):1380–86. ![]()

22. Killion L, Hughes SO, Wendt JC, et al. Minority mothers’ perceptions of children’s body size. International Journal of Obesity 2006;1(2):96–102. ![]()

23. Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Fulkerson JA, Crow S, Neumark-Sztainer D. Eat this, not that! Parental demographic correlates of food-related parenting practices. Appetite 2013;60(0):140–147. doi:![]() .

.

24. Eneli I, Crum P, Tylka T. The trust model: A different feeding paradigm for managing childhood obesity. Obesity 2008;16:2197–204. ![]()

25. Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F, Tedeschi S. Determinants of children’s eating behavior. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011;94(6 Suppl):2006S–2011. doi:![]() .

.