The Role of Text Messages in Patient-Physician Communication about the Influenza Vaccine

The Role of Text Messages in Patient-Physician Communication about the Influenza Vaccine

Disha Kumar1, BS, BA, Vagish Hemmige2,3, MD, MS, Michael A. Kallen4, PhD, MPH, Richard L. Street Jr.2,5,6, PhD, Thomas P. Giordano2,5, MD, MPH, Monisha Arya2,5, MD, MPH

1School of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, TX 77030, U.S.A.; 2Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, U.S.A.; 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, 3411 Wayne Avenue, Suite 4H, Bronx, NY 10467, U.S.A.; 4Department of Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 303 E Chicago Ave, Chicago, IL 60611 U.S.A.; 5Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, 2002 Holcombe Blvd (Mailstop 152), Houston, TX 77030, U.S.A.; 6Department of Communication, Texas A&M University, 4234 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843, U.S.A.

Corresponding author: disha.kumar@bcm.edu

Journal MTM 7:2:55–59, 2018

Background: Racial and ethnic minorities face disparities in receiving the influenza vaccination. A text message intervention could deliver personalized and timely messages to counsel patients on asking their physician for the vaccination.

Aims: We assessed whether patients would be receptive to influenza vaccination text messages.

Methods: Participants were recruited from a sample of low-income, racial and ethnic minority primary care patients. Participants completed a self-administered survey. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data.

Results: There were 274 patients who participated and answered the questions of interest, of whom 70% were racial and ethnic minorities and 85% owned a cell phone. Thirty-six percent reported they had never received an influenza vaccination recommendation from their physician. However, 84% would be comfortable asking their physician for the influenza vaccination. Of cell phone-owning participants who would be comfortable asking their physician about the influenza vaccination, 80% would also be comfortable receiving a text message reminder.

Conclusion: Text messages may be an acceptable channel to prompt patients to discuss the annual influenza vaccination with their physicians. Text messaging is a feasible tool to engage patients in their health and improve annual influenza vaccination rates among low-income, racial and ethnic minority patients.

Key words: minority health, healthcare disparities, telemedicine, mHealth, text messaging, influenza vaccination, health communication

Introduction

Text messages may be an effective solution for improving unacceptably low influenza vaccination rates.1 In the U.S. 2017 early-influenza season, only 38% of adults received the influenza vaccine, with 36% of Hispanic adults, 40% of non-Hispanic Black adults, and 38% of non-Hispanic White adults receiving the vaccine.2 In comparison, 41% of adults received the influenza vaccine during the 2016 early-influenza season.2 As recommended by the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, all adults should receive annual influenza vaccination3 to prevent against the life-threatening effects of influenza. The low vaccination rate during the 2017 early-influenza season may in part have led to the relatively high incidence of influenza illness. During the recent 2017-2018 influenza season (1 Oct 2017 to 03 Feb 2018), the weekly percentage of outpatients visits for influenza-like illness ranged from 1.3% to 7.7%, well above the 2.2% national baseline for the prior three seasons.4

The push-pull capacity model5,6 could be adapted to improve influenza vaccination communication between patients and physicians. In this context, an intervention “pushing” the patient to ask their physician about the influenza vaccination may then “pull” the physician into talking about or recommending the vaccine. Arya et al. have illustrated how the push-pull model using text messages could improve communication about and demand for preventive health services.7 As racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to have poorer communication with their physicians,8 adapting the push-pull model using text messages may help improve this communication especially among these groups. Text messaging-based health campaigns have been successful at engaging patients in preventive health behaviors.9 Despite this success, text messages are underutilized in pushing health information to patients to engage them in managing their own health and in particular, improving patient-physician communication. Due to the ubiquity of text messaging, a text message campaign could help reduce the digital divide, which has left certain groups – such as racial and ethnic minorities – with less access to health information.10

Studies have demonstrated that text messages can help improve influenza vaccination rates; however, these studies have focused on improving childhood vaccination (by texting parents) or improving vaccination among pregnant women.11,12 To date, there has been limited research among low-income racial and ethnic minority adults on using text messages to improve patient-physician communication about vaccination. The purpose of this study was to determine if racial and ethnic minority adult patients who had not received an influenza vaccination recommendation would be comfortable 1) receiving a cell phone text message reminder about the vaccination and 2) asking their physicians for the vaccination.

Methods

This study was conducted June 2014 – February 2015 in a primary care clinic that serves low-income, mostly uninsured racial and ethnic minority patients. We recruited a convenience sample of patients to participate in a self-administered survey developed by the research team. Before study initiation, 38 patients pilot-tested the questions to ensure survey comprehensibility. In addition to survey questions on demographics and cell phone ownership, the primary questions were: 1) “Has your doctor at this clinic ever recommended that you get a flu shot?” 2) “How comfortable would you be asking your doctor for the flu shot?” and 3) “Would you be comfortable receiving a text message reminder about the flu shot?” Participants were given a $10 gift card for participating. The Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis. The responses “no” and “did not remember” for question one were combined into the single response category “no.” The responses “comfortable” and “very comfortable” for question two were combined into the single response category “comfortable.” Similarly, the responses “somewhat comfortable” and “not at all comfortable” for question two were combined into the single response category “not comfortable.”

Results

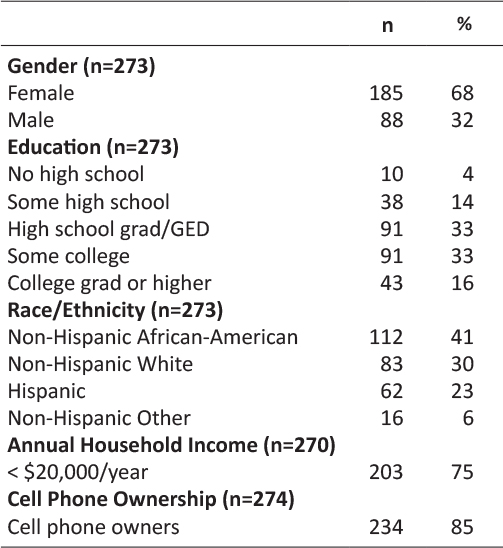

We report data from the 274 participants who answered all three primary questions. Not all 274 participants answered all demographic questions. Of those who answered, the majority were female, had less than a college education, were racial and ethnic minorities, had an income under $20,000/year, and owned a cell phone. Of the 272 participants who responded to age, the median age was 54 years old (Interquartile range: 46-59 years old). See Table 1 for demographic characteristics of study participants.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the study population (N=274)

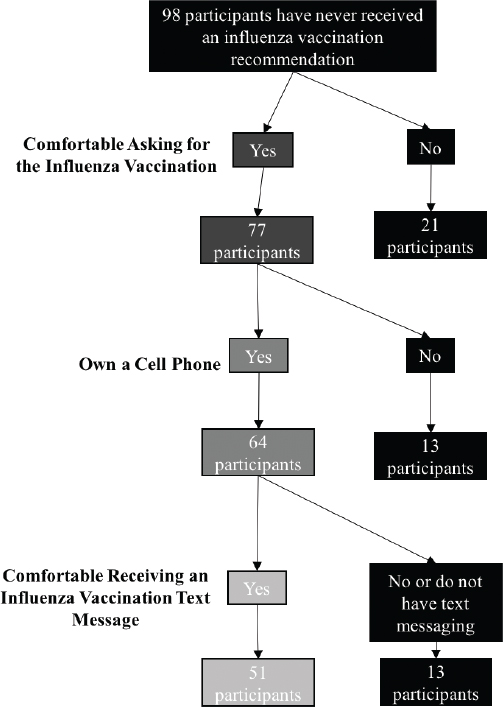

Overall, 98 (36%) had never received an influenza vaccination recommendation from their physician, 230 (84%) would be comfortable asking their physician for the vaccination, and 176 of 234 (75%) cell-phone owning participants would be comfortable receiving a vaccination text message reminder. See Table 2. Of the 98 (36%) participants who indicated they had never received an influenza vaccination recommendation, 77 (79%) would be comfortable asking their physician for the vaccination. Of these 77 participants, 64 (83%) owned a cell phone. Fifty-one (80%) of these 64 participants would be comfortable receiving an influenza vaccination text message reminder. Thus, overall 51 of 98 (52%) participants who had never received an influenza vaccination recommendation would be comfortable asking their physician for the vaccination and may be prompted by a text message to do so. See Figure 1.

Table 2: Results of survey questions pertaining to receiving the influenza vaccination (N=274)

Figure 1: Acceptability of an influenza vaccination text message among participants who have never received a vaccination recommendation from their physician.

Discussion

Interventions are needed to improve vaccination rates, particularly among racial and ethnic minority populations who are traditionally underserved in healthcare. In our study of mostly racial and ethnic minority adults, over one-third of patients did not receive or did not remember receiving an influenza vaccination recommendation from their physician. This highlights the need for strategies to improve vaccination communication between these patients and their physicians. Notably, over three-fourths of patients who had never received an influenza vaccination recommendation from their physician and would be comfortable asking their physician for the vaccination, would also be comfortable receiving the corresponding text message reminder.

Text messages may be particularly suitable for delivering vaccine information in healthcare settings. Texts can be tailored and delivered at a highly pertinent time, such as immediately before a patient enters the examination room. An example of a personalized text message could be: “John, even healthy adults can get the flu and spread it to loved ones. Remind Dr. Jones at your appointment today to talk to you about your yearly flu shot.” This personalized and timely campaign may be more influential at prompting patients to ask for the influenza vaccination than static and non-personalized campaigns. Static campaigns, epitomized by posters in a clinic, may simply go unnoticed among a sea of signs, may not be relatable to the specific patient, or may fail to convince patients who have not already received their annual influenza vaccination. Another benefit of a text message campaign is that it can be integrated into the existing electronic medical record (EMR). Many EMR systems have the capability to send text messages. EMRs are able to extract patient name, physician name, appointment date and time, patient phone number, and lack of receipt of influenza vaccination – all of which can be used to personalize the text message. Thus, the EMR could both personalize and automate text message delivery to patients before a scheduled appointment. For healthcare systems that already use the EMR for appointment reminders, an influenza vaccination campaign could complement the existing reminder. In sum, text messages offer significant opportunity to cost-effectively improve influenza vaccination rates.

While this study offers insight into a strategy to improve influenza vaccination, there are limitations to our findings. Limitations to this study include a relatively small sample size consisting of predominately racial and ethnic minorities and collection of data from one study site. Thus our findings may not be generalizable to other populations. However, our findings may be salient for improving influenza vaccination rates among racial and ethnic adults. An additional limitation is our method of convenience sampling. This may have resulted in a response bias from participants already more inclined to engage in their health; our study sample may therefore be overrepresented by participants willing to talk to their physicians and to receive text message reminders. Our proposed intervention of using text messaging to encourage patient-physician communication about vaccination may therefore be most useful for patients who already actively participate in their health.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a text message could “push” patients to “pull” their physicians into an influenza vaccination discussion, a step needed to improve vaccination rates among adults. This type of text message campaign could help achieve Healthy People 2020 goals of increased patient-physician communication, greater use of health communication technologies, and increased influenza immunization rates.13 Research is still needed to determine the optimal text message content to best persuade patients about their need for annual influenza vaccination and cue them to engage in an influenza vaccination conversation with their physicians. Physician ordering of the vaccination after a patient prompt would also need to be assessed to provide empirical evidence supporting the push-pull model for influenza vaccination.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Trenary, Sajani Patel, and Ashley Phillips for their contributions to data collection. We would also like to thank Haley Marek for her thoughtful contributions to the manuscript draft.

D. Kumar contributed to literature reviews, study design, data collection and analysis, and the writing of all sections. V. Hemmige contributed to data analysis and the writing of the methods and results sections. M.A. Kallen and R.L. Street contributed to study design. T.P. Giordano contributed to study design and data analysis. M. Arya planned the thematic content and study design, and contributed to data analysis and the writing and editing of all sections. All authors contributed to draft versions of the manuscript and provided editorial suggestions for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Some of the results presented in this manuscript were presented in a poster at the March 10, 2016 Henry J.N. Taub/James K. Alexander Medical Student Research Symposium at the Baylor College of Medicine.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH094235 (PI: Arya). This work was supported in part by the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or Baylor College of Medicine.

Financial Disclosures: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Research Involving Human Participants: This study was conducted under approval of Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board Protocol H-30232. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

1. Phillips AL, Kumar D, Patel S, Arya M. Using text messages to improve patient–doctor communication among racial and ethnic minority adults: An innovative solution to increase influenza vaccinations. Prev Med. 2014;69:117–119. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.009 ![]()

2. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Early-Season Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, November 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/nifs-estimates-nov2017.htm. Accessed March 17, 2017.

3. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2017–18 Influenza Season.; 2017:1–20. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/rr/rr6602a1.htm. Accessed March 17, 2018.

4. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Influenza Activity — United States, October 1, 2017–February 3, 2018.; 2018:169–179. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6706a1.htm?s_cid=mm6706a1_w. Accessed March 17, 2018.

5. Curry SJ. Organizational interventions to encourage guideline implementation. Chest. 2000;118(2 Suppl):40S-46S. ![]()

6. Orleans CT. Increasing the demand for and use of effective smoking-cessation treatments reaping the full health benefits of tobacco-control science and policy gains–in our lifetime. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6 Suppl):S340–348. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.003 ![]()

7. Arya, M., Kumar, D., Patel, S., Street, R.L., Giordano, T.P., Viswanath, K. Mitigating HIV Health Disparities: The Promise of Mobile Health for a Patient-Initiated Solution. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2251–2255. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302120 ![]()

8. Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):146–152. ![]()

9. Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040 ![]()

10. Chang BL, Bakken S, Brown SS, et al. Bridging the digital divide: reaching vulnerable populations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(6):448–457. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1535 ![]()

11. Hofstetter AM, Vargas CY, Camargo S, et al. Impacting delayed pediatric influenza vaccination: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):392–401. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.023 ![]()

12. Stockwell MS, Westhoff C, Kharbanda EO, et al. Influenza vaccine text message reminders for urban, low-income pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104 Suppl 1:e7–12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301620 ![]()

13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default. Accessed March 17, 2018.