“Hell, Yeah!” A Qualitative Study of Inpatient Attitudes towards Healthcare Professionals’ Use of Mobile Devices

Lori Giles-Smith BA (Hons), MLIS1, Andrea Spencer RN, BN2

1University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

2Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Corresponding Author: lori.giles-smith@umanitoba.ca

Background: A 2017 study by Giles-Smith et al examining nurse use of and attitudes towards mobile devices at the bedside revealed nurses were reluctant to use mobile devices due to concerns patients would view such device use negatively.

Aims: To explore whether the concerns expressed in the 2017 study regarding mobile device use by healthcare professionals were valid, a qualitative study was conducted to determine patient attitudes towards healthcare professionals’ use of mobile devices at the bedside.

Methods: Short interviews were conducted with 30 inpatients on medical and surgical units at a community hospital in Winnipeg, MB, Canada. Questions captured the inpatients’ socio-demographic data, experiences with healthcare providers using mobile devices during their current stay, and opinions on the use of mobile devices by healthcare providers. The qualitative responses were analysed and coded to determine themes.

Results: Thirty (30) inpatients completed the interviews. Few inpatients reported observing mobile devices use during their current hospital stay. Participants were supportive of the idea of mobile device use in the hospital setting but felt use should be restricted to professional purposes. Results showed a high degree of confidence among patients in the professionalism of their healthcare professionals.

Conclusion: Patients expressed an acceptance of mobile device use in hospitals as a natural extension of the increasing prevalence of technology in modern society. As mobile device use in hospitals increases, healthcare policies that outline acceptable use and protect patient privacy will be necessary. Education will play an important role in improving patient understanding of how mobile devices are used at the bedside.

Keywords: Inpatients, attitude, qualitative research, surveys and questionnaires, mobile devices

Introduction

The medical literature saw a new area of research open up in recent years with health professionals exploring new and potential uses of mobile technologies at the bedside. As researchers and clinicians consider the possibilities for handheld devices in the health sciences, the convenience is clear. Handheld devices are compact and can contain multiple mobile applications including reference books, organizational guidelines, and drug monographs1–3. The ability to provide enhanced communication, point of care tools, and electronic prescribing are just a few other features that allow mobile devices to contribute significantly to safer, more efficient, and higher quality patient care4–7.

A study conducted at the Grace Hospital and Saint Boniface Hospital in Winnipeg, MB, Canada by Giles-Smith, et al 8, examined nurse use of and nurse attitudes towards mobile devices at the bedside. In this 2017 study, nurses reported rarely using mobile devices at the bedside and often expressed ambivalence towards using mobile devices in front of their patients for fear of disapproval and the appearance of unprofessional behaviour. In particular, participants felt elderly patients would not accept nurse use of mobile devices. These opinions, however, were not based on direct input from patients or family members themselves. Similarly, an earlier study by Stroud, Smith and Erkel9 found that nurse practitioners in the United States felt patients would negatively view mobile device use in patient care. A 2020 scoping review by de Jong, Donelle, and Kerr on nurse use of mobile devices also pointed to nurse concerns about patient perception and potential patient complaints.10

There are many articles on mobile devices in healthcare that concentrate on healthcare professionals’ use or assessment of mobile devices and applications in their work8–17. Those that focus on patients often examine the usage of mobile devices by patients as part of mHealth initiatives largely dealing with managing chronic conditions such as diabetes 18–22. Other studies consider patient opinions regarding specific features of mobile technologies. For instance, Seth et al23 discussed patient attitudes towards email communication with their healthcare providers in Southern Ontario. Hsieh et al24 surveyed patients about their feelings regarding usage of mobile devices for photography and general use for reference and communication.

A small number of studies focus on the attitudes of patients towards their healthcare providers using mobile devices at the bedside. In a study of inpatient and caregiver attitudes towards mobile device use in Australia, Alexander et al reported that 73% of survey respondents accepted mobile device use if the doctors were using it for professional and not personal reasons. Patients were more favourable towards doctors using mobile devices than nurses. A major concern from Alexander’s study was that mobile devices distracted both doctors and nurses. There were also participants who thought devices were being used by healthcare professionals for personal or social reasons such as texting and phone calls25.

Blocker, Hayden and Bullock surveyed patients and staff on a trauma and orthopedics department in a teaching hospital in Wales. Of the 59 patients who completed their survey, most (78%) reported never seeing a doctor using a mobile device in the hospital. Those who did see a doctor use a mobile devices believed it to be for work-related communication or educational purposes. No patient thought it was being used for gaming or social media. However, despite the perceived use for professional reasons, most patients (57%) indicated their opinion of their doctor as a professional was negatively influenced by mobile device use. This study found no significant relationship between age of the patient and their opinion of doctors using mobile devices26. A Lebanese study of emergency department patients found 92.6% of study participants felt mobile devices improved healthcare delivery but many patients still did not like their use in the emergency department. Concerns included how it impacted their relationship with the healthcare provider, communication, and potential distraction27.

Illiger et al investigated patients at Hanover Medical School in Germany regarding their acceptance of and use of mobile devices in medical settings. 213 patients were surveyed and most of these (51.6%) owned a mobile device. The majority of patients accepted their doctors using mobile devices but there were concerns about security with 22.3% replying they did not want their doctors to have their individual health-related data on a mobile device and 53.1% were concerned about data protection28. A 2019 study showed that ambulatory patients were more accepting of mobile device use when their physician explained why they were using it29.

Given the juxtaposition of mobile devices as both a potential aid for healthcare professionals and also a potential source of patient disapproval, it is interesting that a significant gap exists in the literature regarding patient perceptions of mobile devices at the bedside. Whether patients feel their healthcare providers are distracted or unprofessional is an important and under-addressed aspect of the discussion on the use of mobile devices in healthcare. While healthcare professionals may express these concerns on behalf of their patients, there are few studies that address whether these perceptions are correct.

The objective of this study is to describe Grace Hospital surgical and medical inpatients’ attitudes and feelings towards healthcare professionals’ use of mobile devices at the bedside. The Grace Hospital, at the time of the study, was a 251-bed community hospital located in Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

Methods

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were 18-years of age or older and had been an inpatient on a medical or surgical unit at the Grace Hospital for at least three days. Patients exhibiting active delirium or dementia and patients in isolation were excluded from the study. A nurse educator not involved in the research project approached eligible patients prior to the interviews. They were given information on the study and asked whether they would be willing to meet with the researchers to conduct a short interview. As an incentive, patients could enter a prize draw to win one of two $100 grocery gift cards.

The researchers conducted patient interviews from March until June 2016. Interviews were guided by a 20-item fixed and open-ended survey developed by the researchers to capture demographic data and attitudes of patients towards healthcare professionals’ use of mobile devices (Appendix A). For the purposes of this study, healthcare professionals were considered to be any person the patient observed working in a professional capacity in the hospital. This included but was not limited to physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals such as pharmacists and occupational therapists. Consent forms were reviewed with the patients and signed at the time of the interviews. Copies of the consent forms as well as information about the project, including the researchers’ contact information, were given to the patients.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (H2015:395 (HS19026)) and Research Access approval was obtained from Winnipeg West

Integrated Health and Social Services. All participants gave informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Results

Descriptive statistics were conducted including frequencies and means for inpatient demographics.

The researchers completed interviews with a convenience sample of 30 inpatients. Patients ranged in age from 25–89 years with the average age being 67 years. The majority of patients were retired. The most common length of hospital stay was 3–10 days. Fourteen (14) patients owned a mobile device and 16 did not. The group was evenly split between males and females.

Only ten (10) of the 30 patients interviewed recalled a healthcare professional using a mobile device in their presence during their current hospital stay. None of these patients had a negative response regarding this usage. When combined with those who were asked how they thought they would feel if they did see such mobile device use, the results were mostly split between those having a neutral reaction (n=15) and a positive reaction (n=12). A minority of participants expressed a negative reaction (n=3) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Reactions towards healthcare professionals’ use of mobile devices.

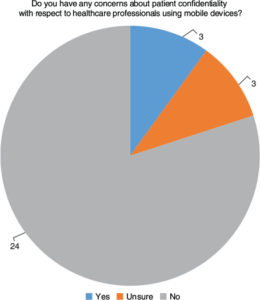

Figure 2: Do you have any concerns about patient confidentiality with respect to healthcare professionals using mobile devices?

When asked if they had any concerns regarding confidentiality with respect to healthcare professionals using mobile devices, the vast majority of participants said they were not concerned (n=24) while three (n=3) were concerned and three (n=3) were unsure (Figure 2).

Using methods described in the nursing literature30–32, the researchers employed content analysis and constant comparison techniques to identify, code, and categorize the qualitative data collected in the inpatient interviews. The researchers developed a coding template and tested it for inter-rater reliability. When the authors disagreed on coding, discussion ensued until consensus was attained. The authors employed the coding template and analyses continued where similar codes were grouped into themes and subthemes.

Five main themes emerged from the qualitative data collected in the patient interviews;

1. Modernization of healthcare: Mobile devices and applications as accepted technology in the modern healthcare environment.

“Hell, yeah! It’s about time . . . the world has stepped up and caught up instead of these misguided beliefs thinking that they should only be used in a closet or something like that. They’re out there to educate, to make people smarter, and if you do not know you can find the answer. They’re there to help. They’re not there to hinder.”

“Caught up with the times.”

“If it was a doctor that had all my health information and my hospital stay, progress, and all that stuff for the health. Well, that’s fine. That’s what they’re for. It’s a new age.”

Patients often expressed the idea that mobile devices are commonplace in modern society and expected this technology to be utilized in hospitals. Patients who embraced this technology themselves enthusiastically expressed their support for mobile devices. Other patients were less inclined to use mobile devices themselves but nonetheless recognized that advances in technology would impact healthcare. Some patients did not seem to understand how this technology worked or felt overwhelmed by the growing pace of mobile devices in society but they still accepted mobile device use as part of advancements in healthcare.

2. Benefits of mobile devices in healthcare: Ideas on how healthcare professionals could use mobile devices in their work and ways in which mobile devices could have a positive impact on healthcare professionals’ work.

“It would reassure me that if they needed to confirm a diagnosis or a treatment or what I’d asked them they were giving me the proper answer.”

“I think it’s much easier than writing everything down and saves on paper.”

“I mean it’s a quick communication and if they need to connect with another area to ask a question about something.”

“Ah, gives them an idea of what the condition of the client is. It allows them to, um, advise the client, ah, what the status is.”

“I think they’re smart . . . because we’re human. We make mistakes.”

Patients had many ideas regarding how healthcare professionals could use mobile devices at work including to communicate with colleagues, record data, and locate medical information. A reoccurring thought was that healthcare professionals would use it to verify information about the patient’s condition, test results, and treatment. A few recalled their experiences with healthcare professionals using mobile devices in their care including as a flashlight and to check for potential drug interactions. Patients cited conveniences such as saving time, ease of use, and reduction of paper. Many of the ideas patients articulated showed that they did not fully understand how mobile devices would be used in patient care. Answers were often vague as patients commented that their doctors would use them for “emergencies”, “information”, and “medications”.

3. Personal use: Thoughts and feelings regarding healthcare professionals using mobile devices for personal versus professional reasons.

“I mean, I don’t expect you people to ignore your families, you know.”

“Ohhhhhh, if they are married they’re checking on the kids! [laughs] I mean, that’s natural!”

“Could be negative if they, say, if you are talking to them and they pull out their phone and start texting but I could see them not doing that. I don’t think they would at least.”

“I don’t think they should use it for personal use while they are on the job.”

Patients gave some surprising answers regarding healthcare professional’s use of mobile devices at work for personal reasons. While most felt mobile devices should only be for professional purposes, some patients assumed healthcare professionals would use their mobile devices to check in with family and were comfortable with that type of usage. Other patients felt healthcare professionals could use mobile devices for personal reasons at work as long as it was not in front of their patients or when they were on a break. Most patients, however, firmly expressed that mobile device use for personal reasons had no place in the healthcare setting. Many stated they would be uncomfortable if mobile devices were used in front of them for personal reasons.

4. Professionalism: Professional behaviour of healthcare professionals regarding mobile devices in the workplace.

“I think they use it in good faith.”

“Well, you would think if they be us-, be using them, they would be under the same rules and conditions that anything else they would be doing.”

“I don’t care what they do as long as they look after me.”

Patients placed a high degree of trust in their healthcare professionals with respect to the use of mobile devices and did not expect healthcare professionals to misuse mobile devices. When patients expressed any misgivings about potential misuses of mobile devices they frequently followed it up by saying they never witnessed any inappropriate use or that they would not expect their healthcare professional to misuse them. Often patients said they would not question mobile device use by their healthcare professionals as they respected their judgment and felt confident that their healthcare professional was taking care of them.

5. Confidentiality: Ideas on whether patient information was secure with mobile device usage.

“Well, they should be accessible by passcode.”

“Confidentiality . . . will not take place if they are using mobile phones or devices like that.”

“Yeah, but that could be with anything. I mean with the records that they got there, how confidential is that? Or if they’re talking there and someone goes by and they hear it. Like, what’s confidentiality?”

“I work a little bit for government and I know all about FIPPA and PHIA and all that so I know that they would have to maintain the same confidentiality that they do already.”

Most responses regarding confidentiality indicated patients wanted their information to be kept private but were not troubled by mobile device use as they expected security systems to be in place to ensure there were no breaches of privacy and data would not be lost. Respondents were often vague when commenting on how privacy would be protected, referring to “firewalls”, “code numbers”, and “passcodes”. One patient pointed out that healthcare professionals were bound by the same privacy regulations if they used mobile devices as they would if they were not using them. No patient expressed concerns over their data being shared over social media or with non-healthcare professionals.

Discussion

In Giles-Smith’s original study on nurse use of mobile devices, nurses expressed a fear that patients would perceive mobile device use unfavourably and view their nurses as disrespectful and unprofessional, especially if the patients felt the mobile devices were being used for personal or entertainment reasons9. The current study was conducted to determine whether these concerns were valid and the results largely disproved these worries. While only one third of patients experienced a healthcare professional using a mobile device in their presence, overall attitudes towards the idea of healthcare providers using mobile devices was favourable. As Illiger et al similarly reported, patients expressed a high degree of confidence in the professionalism of their healthcare professionals28. This was, however, in contrast to research by Blocker, Hayden and Bullock who found that over half of patients viewed device use negatively even if it was being used for professional reasons26.

Many of this study’s findings reinforced results of previous literature on this topic. As in Alexander et al25, patients thought their healthcare professionals would utilize mobile devices for communication and information though a small number also assumed the devices would be used for personal reasons. While some patients at the Grace Hospital felt healthcare providers should be able to use mobile devices for personal use, most did not find this appropriate. Personal use of mobile devices during work time is not acceptable practice for healthcare professionals at the Grace Hospital. Given the number of patients who thought their healthcare professionals would utilize them for personal reasons and the vague responses for why healthcare professionals would use them for professional reasons, education and communication will be crucial as hospitals look to implement policies regarding mobile device use among staff. Patients should understand why their healthcare provider is using a mobile device and be given enough information to feel comfortable when mobile devices are used in their presence. Clearly articulated policies need to be developed, communicated, and implemented that guide device use by healthcare professionals while at work to ensure the benefits of mobile devices are not undermined by negative effects such as distraction, noise, contamination, and breaches of confidentiality30–32.

While recognized as an important issue, patients trusted their information would be kept private and felt security systems would be in place to protect their information. They were less concerned than Illiger’s study group where 22.3% did not want their doctors to have their individual health related data on a mobile device and 53.1% were concerned about data protection28. In addition to how and why the device is being used, healthcare professionals should also advise patients that their confidentiality will not be compromised as a result of such device use. To alleviate any concerns patients do have about confidentiality, institution-provided mobile devices for patient care could be marked to alert patients and family members that the device is hospital sanctioned. This could remove concerns such as picture taking and confidential information being stored on a personal device. It would also reduce inappropriate use through the blocking of social media apps, inappropriate websites, personal email, and texting. To ensure proper use of mobile devices and security of information, healthcare professionals should be reminded of privacy legislation.

As there are limited studies on the subject of patient attitudes toward mobile device use among healthcare professionals, larger studies on this topic are necessary. It would be useful to determine whether there are correlations between age, gender, and ethnicity and attitudes towards mobile device use by healthcare providers. Future studies could explore how healthcare providers could involve patients and families when using mobile devices to promote acceptable use. As stated, one limitation of this study was that it was limited to inpatients on medical and surgical wards. Research involving patients in other hospital departments as well as outpatients would greatly improve our understanding of attitudes towards mobile devices in the healthcare setting. Technology such as mobile devices and applications is ever changing and, as evidenced in this study, patients are recognizing this. Research is required to plan and promote advances in healthcare that utilize this mobile technology for better patient care.

Conclusion

This study revealed the attitudes of medical and surgical inpatients towards their healthcare professionals’ use of mobile devices in a community hospital in Winnipeg, MB. Though few patients experienced mobile device use by healthcare professionals during their hospital stay, results showed that these inpatients were very accepting of mobile device use and placed a significant amount of trust in their healthcare professionals with respect to their usage. Patient responses showed that while they would disapprove of using mobile devices for personal reasons, they trusted their healthcare providers to behave professionally. To ensure patients understand why mobile devices are being used in a hospital setting and to ensure appropriate mobile device use by healthcare professionals, policies and education need to be developed.

Declaration of competing interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: Giles-Smith and Spencer report grant money from Grace Hospital Foundation during the conduct of the study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Grace Hospital Patient Care Research Award sponsored by the Grace Hospital Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge the patients and members of the Patient and Family Advisory Council who took part in interviews and the focus group as well as the hospital managers and administrators who supported this project. The authors would like to thank Dr. Michelle Lobchuk for her guidance during this project and Tracy Martin for facilitating the patient interviews.

Thank you as well to Dr. Elif Acar and Mr. Erfanul Hoque from the Statistical Advisory Service at the University of Manitoba for their general statistics advice and help with the statistical analysis.

References

1. Barton AJ. The regulation of mobile health applications. BMC Med 2012 May;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-46

2. Mosa ASM, Yoo I, Sheets L. A systematic review of healthcare applications for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012 Jul;12:67. doi: 10.1186/ 1472-6947-12-67

3. Yadalla HKK, Vijaya Shankar MR. Professional usage of smart phone applications in medical practice. Int J Health Allied Sci 2012;1:44–6. doi: 10. 4103/2278-344X.101656

4. Williams J. The value of mobile apps in health care. Healthc Financ Manage 2012 Jun;66:96–101.

5. Ventola CL. Mobile devices and apps for health care professionals: uses and benefits. P T 2014 May;39: 356–364.

6. Perna G. Mobility in nursing: an ongoing evolution. Why providers are investing strategically in nursefriendly mobile solutions. Healthc Inform 2012 Aug; 29:16–9.

7. Mickan S, Tilson JK, Atherton H, et al. Evidence of effectiveness of health care professionals using handheld computers: a scoping review of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 2013 Oct;15:e212. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2530

8. Giles-Smith L., Spencer A, Shaw C, et al. A study of the impact of an educational intervention on nurse attitudes and behaviours toward mobile device use in hospital settings. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association / Journal de l’Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada 2017 Apr;38:12–29. doi: 10.5596/c17-003

9. Stroud SD, Smith CA, Erkel EA. Personal digital assistant use by nurse practitioners: a descriptive study. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2009 Jan;21:31–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00368.x

10. de Jong A, Donelle L, Kerr M. Nurses’ use of personal smartphone technology in the workplace: scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e18774. doi: 10.2196/18774

11. Lehnbom EC, Adams K, Day RO, et al. iPad use during ward rounds: an observational study. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;204:67–73 doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-427-5-67

12. McBride DL, LeVasseur SA. Personal communication device use by nurses providing in-patient care: survey of prevalence, patterns, and distraction potential. JMIR Human Factors 2017 Sept;4:e10. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.5110

13. Koivunen M, Niemi A, Hupli M. The use of electronic devices for communication with colleagues and other healthcare professionals – nursing professionals’ perspectives. J Adv Nurs. 2015 Mar;71: 620–31. doi: 10.1111/jan.12529

14. Nerminathan A, Harrison A, Phelps M, et al. Doctors’ use of mobile devices in the clinical setting: a mixed methods study. Intern Med J. 2017 Mar;47:291–298. doi: 10.1111/imj.13349

15. Nguyen HH, Silva JN. Use of smartphone technology in cardiology. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2016 May:26;376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.11.002

16. Johansson P, Petersson G, Saveman BI, et al. Using advanced mobile devices in nursing practice–the views of nurses and nursing students. Health Informatics J. 2014 Sep;20:220–31. doi: 10.1177/ 1460458213491512

17. Gagnon MP, Ngangue P, Payne-Gagnon J, et al. m-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016 Jan;23:212–20. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv052

18. Kessel KA, Vogel MM, Kessel C, et al. Mobile health in oncology: A patient survey about app-assisted cancer care. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017 Jun;5:e81. doi: 10.2196 /mhealth. 7689

19. Van Kessel K, Babbage DR, Reay N, et al. Mobile technology use by people experiencing multiple sclerosis fatigue: survey methodology. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017 Feb;5:e6. doi: 10.2196/ mhealth.6192

20. Martin CK, Gilmore LA, Apolzan JW, et al. Smartloss: a personalized mobile health intervention for weight management and health promotion. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth 2016 Mar;4:e18. doi: 10.2196/ mhealth.5027

21. Silow-Carroll S, Smith B. Clinical management apps: creating partnerships between providers and patients. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2013 Nov;30:1–10.

22. Darlow S, Wen KY. Development testing of mobile health interventions for cancer patient self-management: a review. Health Informatics J. 2016 Sep;22: 633–50. doi: 10.1177/1460458215577994

23. Seth P, Abu-Abed MI, Kapoor V, et al. Email between patient and provider: assessing the attitudes and perspectives of 624 primary health care patients. JMIR Med Inform 2016 Dec; 4:e42. doi: 10.2196/medinform.5853

24. Hsieh C, Yun D, Bhatia C. Ashish, et al. Patient perception on the usage of smartphones for medical photography and for reference in dermatology. Dermatol Surg 2015;41:149–154 doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000213

25. Alexander SM, Nerminathan A, Harrison A, et al. Prejudices and perceptions: patient acceptance of mobile technology use in health care. Intern Med J. 2015 Nov;45:1179–81. doi: 10.1111/imj.12899

26. Blocker O, Hayden L, Bullock A. Doctors and the etiquette of mobile device use in trauma and orthopedics. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015 Jun;3:e71. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4122

27. Alameddine M, Tamim D, Hadid D, et al. Patient attitudes toward mobile device use by health care providers in the emergency department: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(3):e16917. doi:10.2196/16917

28. Illiger K, Hupka M, von Jan U, et al. Mobile technologies: expectancy, usage, and acceptance of clinical staff and patients at a university medical center. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014 Oct;2: e42. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3799

29. Shaarani I, Berjaoui H, Daher A, et al. Attitudes of patients towards digital information retrieval by their physician at point of care in an ambulatory setting. I J Med Inf 2019;130:e103936. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.07.015

30. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008 Apr:62;107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

31. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004 Feb:24;105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

32. Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1986:8;27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005

33. Bautista JR, Lin TT. Sociotechnical analysis of nurses’ use of personal mobile phones at work. Int J Med Inform. 2016 Nov;95:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.09.002

34. Gill PS, Kamath A, Gill TS. Distraction: an assessment of smartphone usage in health care work settings. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2012;5:105–14. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S34813

35. Visvanathan A, Gibb AP, Brady RR. Increasing clinical presence of mobile communication technology: avoiding the pitfalls. Telemed J E Health. 2011 Oct;17:656–61 . doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0018

Appendix A: Survey

Patient Attitudes Towards Mobile Communication

Device Use by Health Care Professionals

Grace Hospital, Winnipeg, MB Definitions for purpose of this survey:

Mobile Device: A portable computing device such as a smart phone or tablet that you can use to access the internet

Mobile Application: Software application designed for mobile devices

ABOUT YOUR MOST RECENT STAY AT THE GRACE HOSPITAL

1. When were you admitted to the hospital?

2. During your stay, did any health care provider use a mobile device in your presence? (If the answer is yes, proceed to question 3. If the answer is no, proceed to question 10)

3. When health care providers used a mobile device in front of you, did they ask your permission to do so?

4. When health care providers used a mobile device in front of you, did they explain why they were using it?

5. When health care providers used a mobile device in front of you, did you feel you understood why they were using it?

6. During your stay, did a health care provider use a smart phone or tablet to answer a question you asked?

7. During your stay, did a health care provider show you their mobile device when explaining something?

8. If a health care provider used a mobile device in front of you, how did you feel?

9. If a health care provider used a mobile device in front of you, do you think it effected how you communicated with them?

10. What do you think when you see a health care professional using a mobile device?

11. Do you have any concerns about patient confidentiality with respect to health care providers using mobile devices?

12. Is there anything else you would like to share about health care providers using mobile devices?

ABOUT YOU

1. What gender do you identify with?

____ Male

____ Female

____ Other

2. What is the highest level of education you have completed?

____ no high school

____ some high school but did not graduate

____ high school or high school equivalency certificate

____ some postsecondary

____ trade, vocational or technical diploma

____ undergraduate degree

____ postgraduate or professional degree

____ prefer not to answer

3. What year were you born?

19 ____

4. What is your annual household income? _____ $0 – 24,999

_____ $25,000 – 49,000

_____ $50,000 – 74,000

_____ $75,000 – $99,000

_____ Over $100,000

5. Employment status. Are you;

____ Employed

____ Retired

____ Currently unemployed

____ Homemaker

____ Student

____ Unable to work

____ Self employed

____ Prefer not to answer

Other ____________________

6. Do you identify with any particular cultural or ethnic group?

7. Do you own a mobile device (e.g., smartphone, tablet)?

8. If you own a mobile device, how important is its use in your daily life?