Internet and smartphone delivery of core trunk exercises for a randomised clinical trial: protocol

Margaret Agnes Perrott, M Sports Physio, M App Sci1, Tania Pizzari, PhD2, Jill Cook, PhD3

1Department of Physiotherapy, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Vic. 3086; 2Department of Physiotherapy, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Vic. 3086; 3Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Frankston, Vic. 3199

Corresponding author m.perrott@latrobe.edu.au

Journal MTM 3:2:46–54, 2014

Background: Lumbopelvic stability exercises are commonly prescribed for athletes to prevent sports injury; however, there is limited evidence that exercises are effective. Exercise trials are time consuming and costly to implement when teaching exercises or providing feedback directly to participants. Delivery of exercise programs using mobile technology potentially overcomes these difficulties.

Aims: To evaluate the qualitative clinical changes and quantitative movement pattern changes on lumbopelvic stability and injury in recreational athletes following exercise. It is hypothesised that athletes who complete the stability training program will improve their clinical rating of lumbopelvic stability, quantitatively improve their movement patterns and have fewer injuries compared to those who complete the stretching program.

Methods: One hundred and fifty recreational athletes will be recruited for the trial. Direct contact with researchers will be limited to three movement test sessions at baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months after baseline. Videoed performance of the tests will be accessed from an internet data storage site by researchers for clinical evaluation of lumbopelvic stability. Those without good stability at baseline will be randomly allocated to one of two exercise groups. The exercise programs will be delivered via the internet. Feedback on correct performance of the exercises will be provided using a smartphone software application. Injury will be monitored weekly for 12 months using text messages.

Conclusion: The trial protocol will establish if an exercise training program improves lumbopelvic stability and reduces injury. Improvement in lumbopelvic stability following an exercise program delivered with mobile technology will enable the provision of exercise programs to other athletes who may be geographically remote from their exercise provider and establish a method for researchers and health professions to use for exercise programs for individuals with other health conditions.

Trial Registration: ACTRN12614000095662

Background

Lumbopelvic stability (LPS) has been defined as the ability of an individual to maintain optimal alignment of the spine, pelvis, and the thigh in both a static position and during dynamic activity1. Clinically, there is a perception that LPS is an essential component of injury prevention, and training LPS is thought to aid recovery from injury and improve performance2. Deficits in LPS have been associated with injury or pain in the back, groin and knee3–10 and exercise for the lumbopelvic region can reduce the risk of muscle strain injury11 and improve the gold standard quantitative measure of movement: three dimensional kinematics12,13.

Although evidence demonstrates that the performance of single leg squat (SLS), a key measure of LPS, can be changed by exercise12, it is uncertain if a training program focused solely on LPS can improve an athlete’s qualitative clinical rating of LPS when assessed by physiotherapists or will be validated by improved kinematic measures. It is also uncertain if isolated LPS training reduces the risk of injury. This trial aims to establish whether an LPS exercise program improves an athlete’s qualitative and quantitative performance of specific LPS tests and whether injury is reduced by improvement in LPS.

A barrier to implementing randomised controlled clinical exercise trials is the time consuming and costly nature of teaching exercises directly to research participants14. The use of mobile technology has the potential to overcome these barriers and to standardise the exercises that are taught15. This trial will use mobile technology, both internet and smartphone, in delivery of exercise programs, for providing feedback on exercise technique and for injury monitoring.

Methods

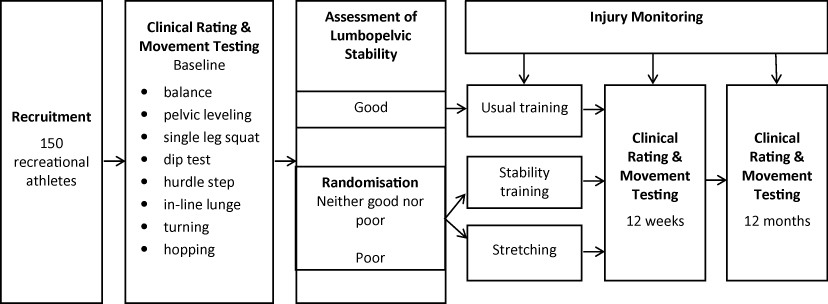

A single-blinded parallel randomised controlled trial (Figure 1) will compare the effect of two exercise programs in participants who have deficient LPS. The trial protocol has been approved by the La Trobe University Faculty Human Ethics Committee and all participants will give informed consent before taking part (Reference: FHC13/121) and registered with Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12614000095662).

Figure 1: Participant flow chart

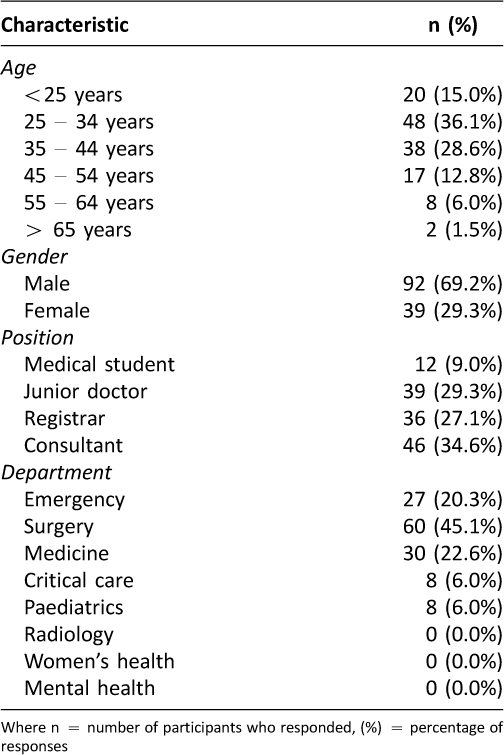

Rating of Lumbopelvic Stability

One hundred and fifty healthy male and female recreational athletes will be recruited for a randomised controlled clinical trial. They will complete baseline movement testing of eight movement tests. Performance of two tests: SLS and dip test will be videoed by the lead researcher (MP) and uploaded to a Dropbox™ shared with two other researchers (T.P., J.C.). To protect the security of data, Dropbox uses Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and AES-256 bit encryption to transfer and store data16, making this an ethically acceptable way for the researchers to view the video performance.

The researchers will rate the individual’s LPS as good, poor or neither good nor poor. The rating classification system has been previously validated17. Rating LPS using video eliminates the need for the raters to be present at each movement test or for the participants to perform the tests multiple times for individual raters. This method has been used previously by these researchers17,18 Individuals classified as having good lumbopelvic stability will continue their usual training. All other participants will be randomly allocated to one of two exercise groups focused on the lumbopelvic region: stability training or stretching program. The exercise programs run for 12 weeks and are performed 3 times per week at home. The exercises take less than 15 minutes to perform. Allocation to exercise groups will be performed immediately after the clinical rating of LPS. Group allocation will be concealed by using an off-site trial administrator who holds the randomisation schedule. This administrator will not have any other role in the trial.

Randomisation

Stratified-block randomisation in groups of 20 will be performed using a random sequence generator at http://www.random.org/sequences. Stratification will be based on clinical rating of LPS: poor or neither good nor poor. This randomisation will ensure that similar numbers of participants with poor LPS or neither good nor poor LPS will be randomised to each exercise group. Differences in baseline LPS may influence the outcome of the trial rather than the intervention alone19.

Blinding

The researchers rating the LPS of participants at the 12 week and 12 month post intervention testing will be blinded to group allocation. The researchers assessing the outcomes and analysing the results data will also be blinded to group allocation.

Movement testing

Participants will attend three testing sessions, baseline, at the completion of the intervention at 12 weeks, and 12 months after baseline testing, to evaluate movement patterns in eight movement tests. This testing will be performed using the Organic Motion system (Organic Motion, New York, USA). This system records movement with gray scale cameras (120 Hz), develops a morphological and kinematic model of the participant, generates a body shape and matches it with a joint centre model from which angular changes in body segments can be extracted20. The system can report details of movement characteristics known to discriminate between good and poor LPS17.

Movement Tests

Eight movement tests have been chosen for the trial as they challenge control of the lumbopelvic region and their performance may be influenced by improvement in LPS. Six have previously been described: balance on one leg with eyes closed21,22, SLS23, dip test24, hurdle step and in-line lunge25 and side-to-side hopping26. Two additional tests will be performed: a turning manoeuvre and a pelvic leveling test. The turning manoeuvre will replicate typical sporting activity27 with the participants performing a running v-shaped turn. The pelvic leveling test is based on tests of postural control 28 where the participant stands on one leg, raises and lowers one side of their pelvis and attempts to return their pelvis to a level position. Participants will warm-up with 5 minutes walking at a comfortable speed on a treadmill while watching a video on correct performance of the tests, and then practice each test. The tests will be performed on each leg in random order.

Baseline Testing

1. Clinical assessment

The performance of SLS and dip test will be rated for LPS. Three other tests: balance, hurdle step and in-line lunge will be videoed and a clinical score recorded using validated rating systems. The balance test is scored with a point for each of 6 possible error types using the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS), with zero being the best possible score21. Hurdle step and in-line lunge are both scored from zero to three, with three being the best possible score25.

2. Kinematic assessment

Kinematic measures of three planes of movement of the back, pelvis and thigh will be recorded during the eight movement tests using the Organic Motion markerless motion capture system.

Follow-Up Testing

The same assessment of clinical rating of LPS, clinical scores from 5 movement tests and kinematic measures from all movement tests will be performed for all participants at 12 weeks and 12 months after their inclusion in the trial, including those with good LPS who are continuing their usual training.

Adherence and Injury Monitoring with Mobile Technology

Mobile telephone technology (text messaging) will be used to collect data on exercise adherence and to monitor sporting injuries during the 12 months of the trial. Weekly text messages will be sent to all participants. During the exercise programs the participants will be asked via text message how many times they have performed the exercises that week, with the options of replying “0”, “1”, “2”, or “3”. Also throughout the trial they will be asked if they have sustained a sports injury during the week, with the option to reply “injury” or “no injury”. Therefore, for example, they may reply “3 no injury”. This simple text message response mechanism will assist in keeping participants engaged in the trial with encouragement for prompt reply being rewarded by entry into a weekly prize draw. External observation by text message communication is expected to increase the commitment of participants to perform the exercises29. If participants reply that they have been injured the lead researcher will contact them via phone to identify the nature of the injury and refer them to an appropriate health practitioner for treatment.

Mobile Delivery of Exercise Programs and Feedback

After LPS rating, participants will be randomised to an exercise group. The exercise programs will be delivered to the participants with a link to one of two Dropbox internet sites: one for stability exercise and one for stretching exercise. At the site participants will access two types of video file: first, preliminary instructions and second, video of each exercise routine. The preliminary instructions include examples of correct technique and the number of repetitions to be performed. The stability exercise video also includes instructions on how to progress the exercises through four levels of difficulty. The exercise routine videos show exact timing and technique and allow the participant to exercise in conjunction with the video, providing a model to match. Participants will also be given written instructions and a poster showing either the stability exercises or the stretching exercises and the numbers of exercises and sets to be performed.

Feedback on correct exercise technique will be provided using an app, Coach’s Eye (TechSmith Corporation, Michigan, USA), that can be downloaded to smartphones, iPad and tablets. This app provides visual and verbal feedback on exercise technique that is provided directly to the participant’s smart phone. The system is operational on iOS, android and windows operating systems. The app provider has established a list of recommended devices on which the app is fully operational. If a participant has a smart phone that does not function correctly with the app, the participant will be able to video their performance on their phone, send to the lead researcher and receive visual feedback via email image that is indistinguishable from the Coach’s eye app. Written feedback will also be given in the email. Consistency of feedback across participants is regarded as important so that participants are able to access the same level of involvement in the project29. Feedback on exercise technique will be available at any time during the 12 week exercise program and will give participants the opportunity to report difficulty with performance of the exercises.

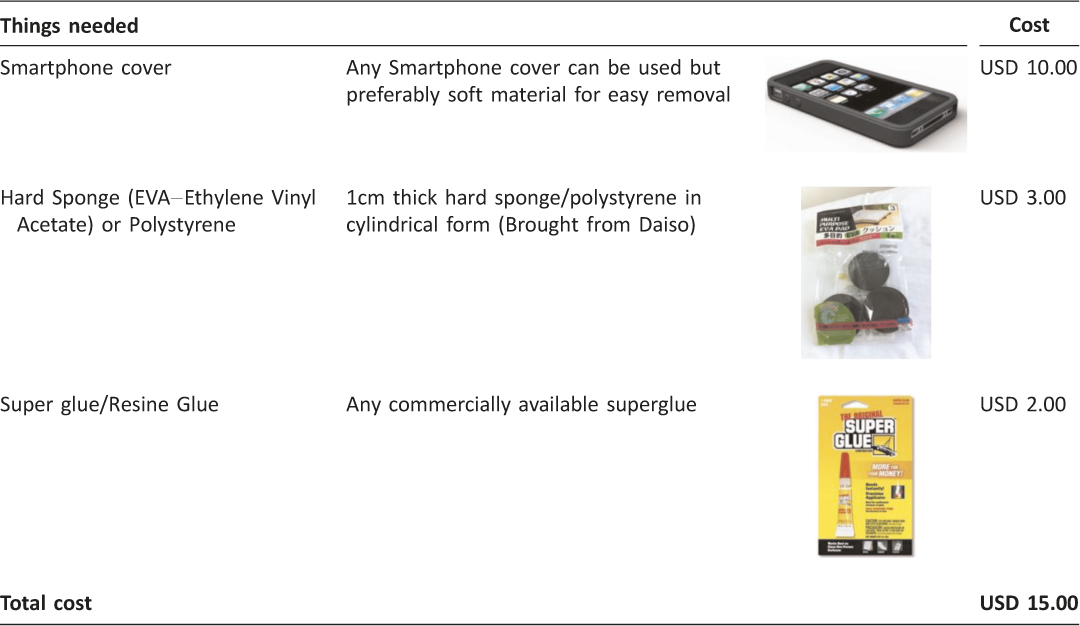

Stability Training Program

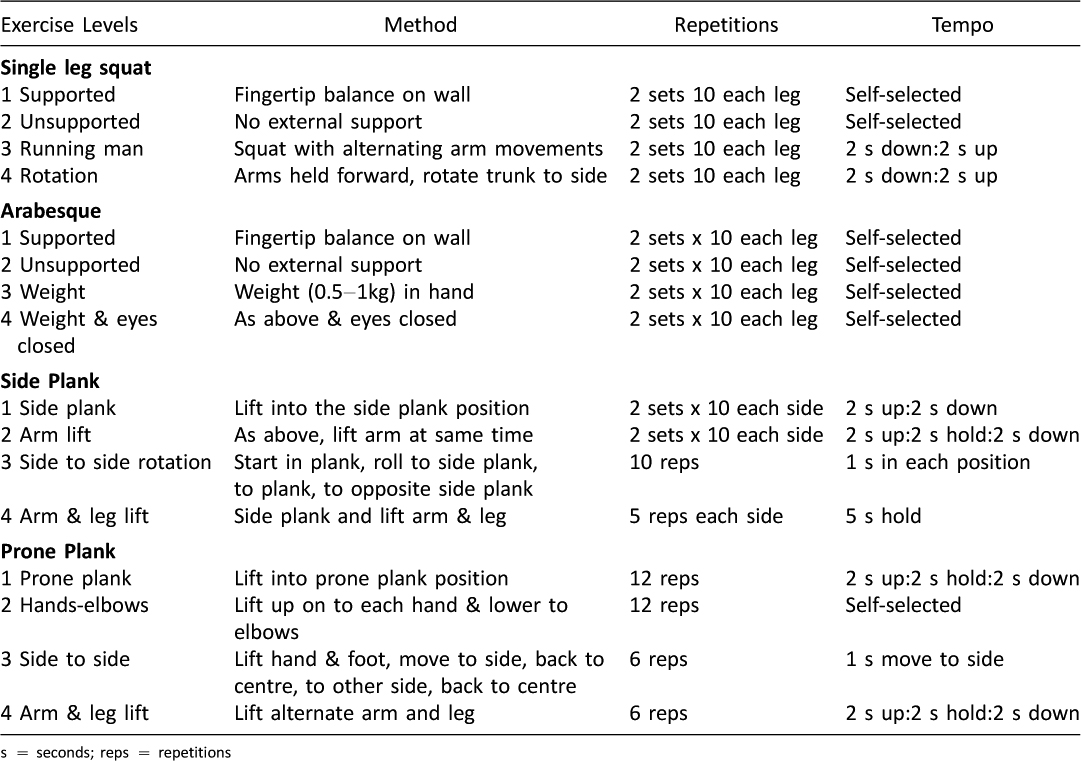

The participants allocated to this group will be asked to perform a 12 week LPS training program 3 times per week at home (Table 1). They will perform 1–2 sets of 5–12 repetitions of the exercises.

Table 1: Stability training program

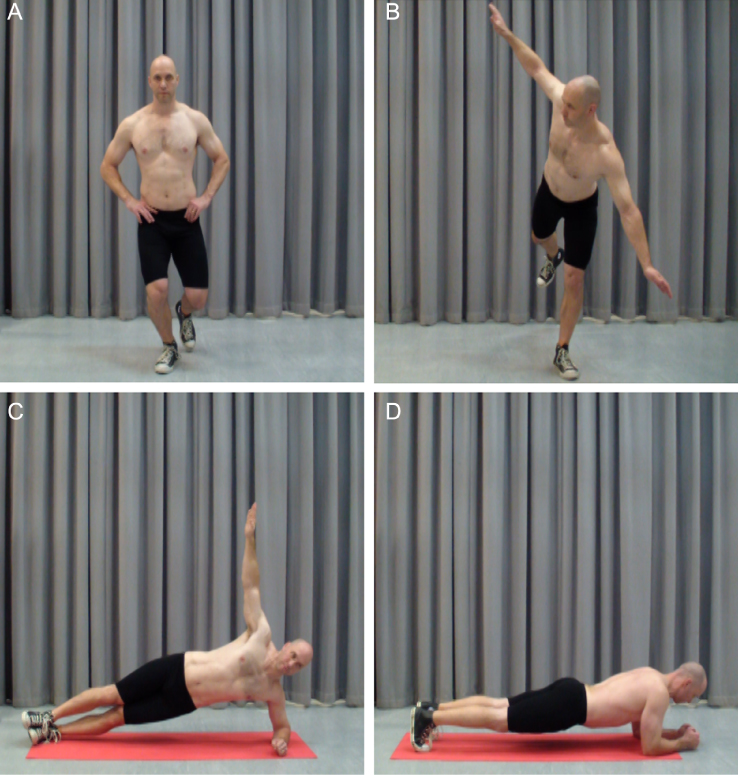

The stability training program comprises four exercises, each of which has four levels. The exercises are SLS, arabesque, side plank and prone plank (Figures 2a–d).The exercises commence in well-supported positions, performing only small movements and progress to increasingly challenging exercises with larger ranges of movement in positions that challenge LPS. Each exercise has criteria describing competent performance. The participants will progress at their own rate to the next level when competent at that level. Participants may not reach the highest level of each exercise during the 12 weeks.

Figure 2: Stability exercises a. Single leg squat, b. Arabesque, c. Side plank, d. Prone plank

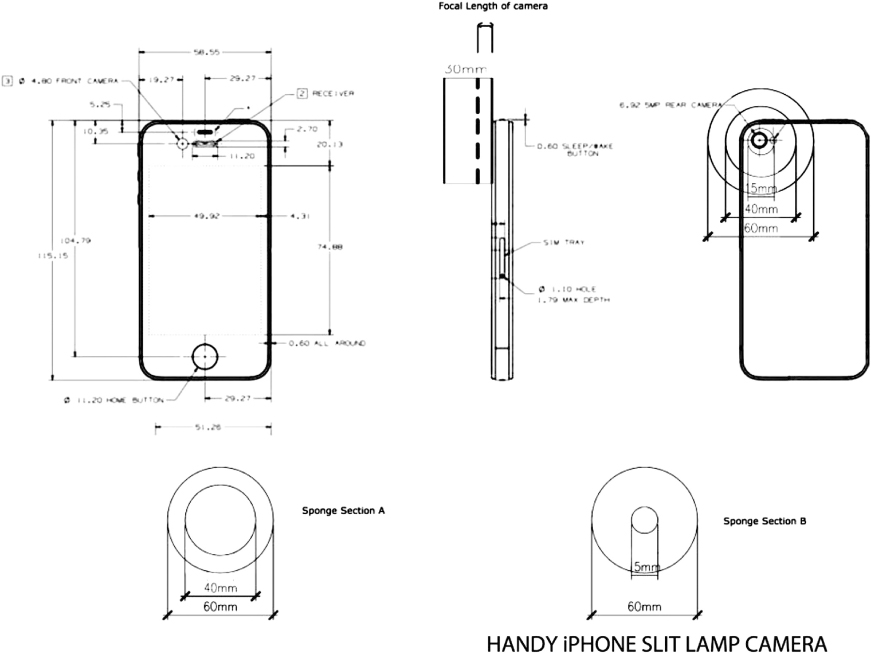

Stretching Training Program

The participants allocated to this group will be asked to perform a 12 week stretching training program 3 times per week at home. The stretching training program comprises stretches for six muscle groups attached to the lumbopelvic region: hamstrings, quadriceps, adductors, gluteals, trunk rotators and hip flexors (Figures 3a–f) and have been described previously30. The participants should feel a strong but comfortable stretch and hold each stretch for 30 seconds. The stretches will be performed on each side.

Figure 3: Stretching exercises a. Hamstrings, b. Quadriceps, c. Adductors, d. Gluteals, e. Trunk rotators, f. Hip flexors

Power calculation: sample size

One hundred and fifty recreational athletes will be recruited. The sample size is based on the clinically relevant ability to detect change in lumbopelvic stability after stability training in those with poor stability. Previous research shows a range of sample sizes from 21–42 where stability training changed isolated aspects of LPS7, 31, 32, or reduced pain and disability33.

This sample size range is supported by a power calculation based on research investigating the effect of a stability and agility program compared to a stretching program on recurrent hamstring strain34. To detect differences between the two interventions in the current study and achieve a power of 0.8 at an alpha level of 0.05, df = 1, using chi square, a sample size of 19 with poor LPS would be required35. This sample size is likely to be insufficient for the current study since the hamstring study was limited to a specific population with a high risk of re-injury who were closely supervised in their performance of their exercise program. Therefore a larger sample size will be chosen for the current trial.

A sample size of 150 participants should yield 34 participants with poor LPS. This is based on a study by the current researchers that yielded 14 individuals with poor LPS, 9 with good LPS and 39 with neither good nor poor stability from a population of 62 recreational athletes17. This should ensure a large enough sample size to detect change in LPS in those with poor LPS. The power of the trial is increased by basing the sample size only on detecting change in those with poor LPS, as change in LPS in those with neither good nor poor stability will also be examined in this trial.

Data analysis: clinical rating

Clinical rating of LPS (good, poor or neither good nor poor) will be compared before and after intervention using Chi square. Performance scores for balance, hurdle step and in-line lunge will be compared before and after intervention using Friedman two-way analysis of variance by ranks.

The correlation between clinical LPS rating and performance scores will be analysed using Spearman rho at baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months to establish if there is an association between clinical rating and performance scores on other tests. The alpha level will be set at p ≤ 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Data analysis: kinematic measures

Kinematic measures related to lumbopelvic stability will be compared before and after intervention using mixed two-way ANOVA (group by time). This comparison will be made at baseline, 12 weeks and 12 months to determine if an exercise program changes the amount that athletes move. Movement patterns will be analysed on each leg with skill and stance legs36 analysed separately.

Data analysis: injury rate and adherence

The association between baseline rating of LPS and subsequent sports injury will be analysed using Chi square. Adherence to the exercise programs will be reported as a percentage of the 36 expected exercise sessions. Exercise adherence will be used as a covariate in analysis of change in clinical rating and injury rate.

Conclusion

This randomised controlled trial will examine the effectiveness of an exercise program designed to improve LPS compared to a control exercise program in recreational athletes. It is expected that the stability program will be more effective in improving LPS, changing movement patterns and reducing injury than the stretching program.

The trial is dependent on the use of mobile technology, both internet and smartphone, to deliver the exercise program instructions and technique, to provide feedback on exercise technique and to monitor exercise adherence and injury. Exercise trials that rely on teaching exercise programs face to face or that require participants to attend exercise groups are expensive and time consuming to conduct for both researchers and participants. The use of text messages simplifies the process of monitoring adherence and injury rather than the use of exercise/injury diaries. The ability to deliver the randomised controlled trial in a time and cost effective manner has implications for first, the specific outcome of this trial on lumbopelvic stability and second, for exercise trials for other health conditions. If the LPS exercise program is successful in changing LPS and also in reducing injury this provides an effective method to make the exercise program available for the general sporting community. It would also be possible for individuals to perform the important movement tests that enable them to be classified as having good, poor or neither good nor poor LPS at home and send them via the Coach’s Eye app to be assessed. If they do not have good LPS they could be provided with the stability exercise program via the internet and receive feedback with the app. This enables athletes who are geographically remote from skilled physiotherapists to access proven exercise techniques for their LPS. In addition to the direct outcome of this trial, other researchers or health professionals can use the methods in this protocol to establish exercise programs for other health conditions by videoing correct performance of exercise technique to deliver the exercise programs and provide feedback using mobile technology.

The trial will be reported in accordance with the CONSORT group statement.

Trial status

At the time of manuscript submission recruitment of participants had not commenced.

General Disclosure Statement

Ms Perrott and Dr. Pizzari have nothing to disclose. Prof. Cook reports a relevant financial activity outside the submitted work as a director of company that has interests in tendon imaging and management.

Video Links

References

1. Perrott M, Pizzari T, Cook J, Opar MS. Development of clinical rating criteria for tests of lumbo-pelvic stability. Rehabilitation Research and Practice [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2012 May 29]. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/rerp/2012/803637/.

2. Willardson JM. Core stability training: Applications to sports conditioning programs. J Strength Cond. 2007;21(3):979–85.

3. Biering-Sorenson F. Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one year period. Spine. 1984;9(2):108–19.

4. Bolgla LA, Malone TR, Umberger BR, Uhl TL. Hip strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(1):12–8. ![]()

5. Cowan SM, Schache AG, Brukner P, Bennell KL, Hodges PW, Coburn P, et al. Delayed onset of transversus abdominus in long-standing groin pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(12):2040–5. ![]()

6. Evans C, Oldreive W. A study to investigate whether golfers with a history of low back pain show a decreased endurance of transversus abdominus. J Man Manip Ther. 2000;8(4):162–74. ![]()

7. Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first-episode low back pain. Spine. 1996;21(23):2763–9. ![]()

8. Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21(22):2640–50. ![]()

9. Leetun DT, Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. Core stability measures as risk factors for lower extremity injury in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(6):926–34. ![]()

10. Zazulak BT, Hewett TE, Reeves NP, Goldberg B, Cholewicki J. Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: a prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1123–30. ![]()

11. Perrott MA, Pizzari T, Cook C. Lumbopelvic exercise reduces lower limb muscle strain injury in recreational athletes Phys Ther Rev. 2013;18(1):24–33.

12. Baldon RD, Lobato DF, Carvalho LP, Wun PY, Santiago PR, Serrao FV. Effect of functional stabilization training on lower limb biomechanics in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(1):135–45. ![]()

13. Shirey M, Hurlbutt M, Johansen N, King GW, Wilkinson SG, Hoover DL. The influence of core musculature engagement on hip and knee kinematics in women during a single leg squat. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(1):1–12.

14. McTiernan A, Schwartz RS, Potter J, Bowen D. Exercise clinical trials in cancer prevention research: a call to action. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(3):201–7.

15. Parker M. Use of a tablet to enhance standardisation procedures in a randomised trial. Journal of MTM. 2012;1(1):24–6. ![]()

16. How secure is Dropbox? 2014 [cited 2014 17/5/2014]. Available from: https://www.dropbox.com/help/27/en.

17. Perrott MA. Development and evaluation of rating criteria for clinical tests of lumbo-pelvic stability [electronic resource] [Masters Thesis]. Melbourne: La Trobe University; 2010.

18. Perrott MA, Cook J, Pizzari T, editors. Clinical rating of poor lumbo-pelvic stability is associated with quantifiable, distinct movement patterns. Australian Conference of Science and Medicine in Sport; 2009; Brisbane: Sports Medicine Australia.

19. Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Makuch RW, Brass LM, Horwitz RI. Stratified randomization for clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(1):19–26. ![]()

20. Mundermann A, Mundermann L, Andriacchi TP. Amplitude and phasing of trunk motion is critical for the efficacy of gait training aimed at reducing ambulatory loads at the knee. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134(1):011010. ![]()

21. Finnoff JT, Peterson VJ, Hollman JH, Smith J. Intrarater and interrater reliability of the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS). Pm R. 2009;1(1):50–44. ![]()

22. Riemann BL, Guskiewicz K, Shields EW. Relationship between clinical and forceplate measures of postural stability JSR. 1999;8(2):71–82.

23. Zeller BL, McCrory JL, Kibler WB, Uhl TL. Differences in kinematics and electromyographic activity between men and women during the single-legged squat. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):449–56.

24. Harvey D, Mansfield C, Grant M. Screening test protocols: pre-participation screening of athletes. Canberra: Australian Sports Commission; 2000.

25. Cook G, Burton L, Hoogenboom B. Pre-participation screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – part 1. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2006;1(2):62–72.

26. Itoh H, Kurosaka M, Yoshiya S, Ichihashi N, Mizuno K. Evaluation of functional deficits determined by four different hop tests in patients with anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Knee Surg Sport Tr A. 1998;6(4):241–5. ![]()

27. Muller C, Sterzing T, Lake M, Milani TL. Different stud configurations cause movement adaptations during a soccer turning movement. Footwear Sci. 2010;2(1):21–8. ![]()

28. Stevens VK, Bouche KG, Mahieu NN, Cambier DC, Vanderstraeten GG, Danneels LA. Reliability of a functional clinical test battery evaluating postural control, proprioception and trunk muscle activity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(9):727–36. ![]()

29. Lied TR, Kazandjian VA. A Hawthorne strategy: implications for performance measurement and improvement. Clin Perform Qual Health Care. 1998;6(4):201–4.

30. Herbert RD, Gabriel M. Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and risk of injury: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7362):468. ![]()

31. Hides JA, Stanton W, McMahon S, Sims K, Richardson CA. Effect of stabilization training on multifidus muscle cross-sectional area among young elite cricketers with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(3):101–8. ![]()

32. Stanton R, Reaburn PR, Humphries B. The effect of short-term Swiss ball training on core stability and running economy. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(3):522–8.

33. O’Sullivan PB, Twomey LT, Allison GT. Evaluation of specific stabilising exercises in the treatment of chronic low back pain with radiological diagnosis of spondylolisis or spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1997;22(24):2959–67. ![]()

34. Sherry MA, Best TM. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(3):116–25. ![]()

35. Lenth RV. Java Applets for Power and Sample Size [Computer software]. 2006–2009 [4/4/2014]. Available from: http://www.stat.uiowa.edu/~rlenth/Power.

36. Bullock-Saxton JE, Wong JE, Hogan N. The influence of age on weight-bearing joint reposition sense of the knee. Ex Brain Res. 2001;136(3):400–6. ![]()